National Security Agency whistleblower Edward Snowden, on Sunday, June 9, 2013, in Hong Kong. (AP Photo/The Guardian, Glenn Greenwald and Laura Poitras)

We seem to have reached a moment in the United States when the suspicion arises that law is congealed injustice, that the existing order hides an everyday violence against body and spirit, that our political structure is fossilized, and that the noise of change, however scary, may be necessary.

—Howard Zinn, Disobedience and Democracy: Nine Fallacies on Law and Order (1968)

By leaking classified National Security Agency (NSA) documents that prove the existence of large-scale secret surveillance programs, Edward Snowden has answered the late historian Howard Zinn’s call to reexamine our adherence to laws that prevent rather than promote social justice and democracy. Though Snowden may face charges of treason by going public as a whistleblower, he appears to have decided that the risks he took, however scary, were necessary. As an artist I usually dwell in the realm of the symbolic, reassembling images and texts to affective ends, using empathy to enlarge our experience of political violence. But the consequences of my actions have never put my freedom at risk in the way Snowden has his.

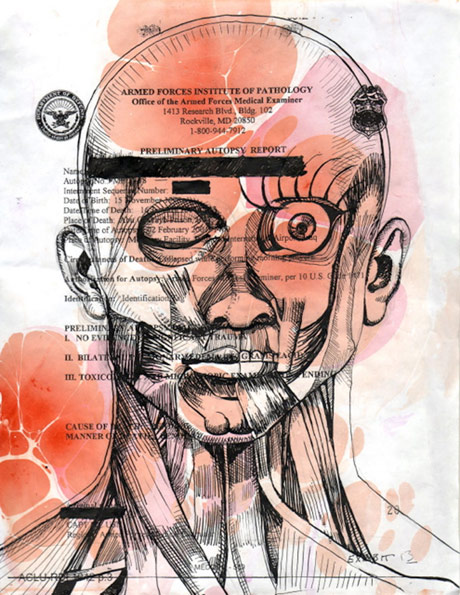

The topic of surveillance came up frequently when I was artist-in-residence at the ACLU’s National Security Project last fall. The residency was designed for me to conduct research on “Did You Kiss the Dead Body?,” an ongoing art project that incorporates U.S. military autopsy reports of Iraqi and Afghan men killed in U.S. custody since 2003 into anatomical drawings. The residency, structured around a set of conversations with lawyers about torture, race, empathy, trauma, truth and justice, went beyond the prisons of Iraq and Afghanistan to detail the many unseen consequences of a global “war on terror.” Over 40 audio segments from these conversations can be found here.

Rajkamal Kahlon, detail of Autopsy No.: ME04-38; pp. 1-11; The teeth appear natural and in good condition, from “Did You Kiss the Dead Body?,” 2012.

It was during my residency that I first met Jameel Jaffer, the Director of the Center for Democracy at the ACLU. At the time, Jaffer was preparing for his first Supreme Court oral argument, Clapper v. Amnesty, representing a group of human rights workers, lawyers and journalists who sought to challenge the government’s secret surveillance of their foreign correspondence, enabled through the 2008 FISA Amendments Act. In previous Creative Time Reports dispatches, I interviewed Jaffer about past and present surveillance in America as well as the specifics of Clapper v. Amnesty. In light of the recent leaks, I asked him to extend our ongoing conversation by participating in a Q&A about the National Security Agency and American surveillance.

Rajkamal Kahlon: Whistleblower Edward Snowden recently revealed documents that show the U.S. has been collecting data on both American citizens and foreign individuals with programs called Boundless Informant and PRISM. What are they and how do they work?

Jameel Jaffer: One set of documents makes clear that the National Security Agency is collecting “metadata” about every phone call made to or from a phone number inside the United States. Under this program, the NSA requires telecommunications companies (Verizon, AT&T, etc.) to turn over information about their customers on a daily basis. The information is quite detailed. As I said when we sued over the program’s constitutionality, the program “is the equivalent of requiring every American to file a daily report with the government of every location they visited, every person they talked to on the phone, the time of each call and the length of every conversation.”

The collection of all of this data is itself an abuse—a gross violation of the right to privacy.

Another set of documents relates to PRISM. This program involves the monitoring of phone calls and electronic communications into and out of the United States. PRISM is based on a 2008 statute that gives the NSA almost unlimited authority to monitor the communications of foreign citizens outside the United States. In the course of that surveillance, the NSA also sweeps up Americans’ international communications, and some unknown quantity of their purely domestic communications as well. The Guardian and the Washington Post recently released the NSA’s “targeting” and “minimization” procedures—the procedures that control what communications the NSA collects in the first place and what it does with those communications once they’re collected.

My understanding is that “Boundless Informant” is not itself a surveillance program but rather a system that allows the NSA to measure the agency’s reach into any given country.

RK: From what we know about the programs, what potential for abuse exists?

JJ: In my view, this is the wrong question. The collection of all of this data is itself an abuse—a gross violation of the right to privacy. This said, it’s certainly true that the creation of these kinds of databases could lead to all sorts of second-order abuses. As I wrote in this New York Times debate, there’s already a great deal of evidence that the government’s surveillance powers are being trained against the wrong targets and used for the wrong purposes:

Here is an article about the Department of Homeland Security conducting inappropriate surveillance of protesters associated with Occupy Wall Street. Here is a report of the Justice Department’s inspector general finding that the F.B.I. monitored a political group because of its anti-war views. Here is a story in which a former C.I.A. official says that the agency gathered information about a prominent war critic “in order to discredit him.”

RK: The Obama administration and the NSA have responded to the leaks by justifying their actions as part of their larger efforts to fight the War on Terror. The debate around these programs often revolves around a trade-off we are asked to make between security, on the one hand, and privacy or liberty on the other. Do you believe these programs may effectively stop terrorist attacks and high-level crime, even if at the expense of civil liberties? And if so, how do you balance these two values, safety and freedom?

JJ: The government hasn’t been able to produce evidence that these programs were crucial to the prevention of any specific terrorist attack. And one reason to doubt that they were crucial is that the government hasn’t relied on evidence derived from these dragnet programs in criminal prosecutions. If the programs were so crucial, why hasn’t anyone been prosecuted on the basis of evidence derived from them?

RK: What were the roles of Verizon, Apple, Google and Facebook?

JJ: These corporations collect information about us. The government asks (or directs) the corporations to turn the information over to it. Some of the corporations resist to a certain extent; others do not resist at all. I haven’t seen any evidence that Verizon resisted the government’s demand that it turn over metadata about all of its customers’ phone calls. To their credit, some of the corporations—Google, Microsoft, and Yahoo, for example—have recently filed legal challenges to the government’s demands or to “gag orders” that prevent them from talking publicly about some of the government’s surveillance activities.

RK: Do the recent leaks have any bearing on the lawsuit filed by the ACLU against the NYPD for the large-scale surveillance of New York area Muslims?

JJ: No direct bearing, but I hope that recent disclosures about the scale of the NSA’s surveillance activities will affect the way the case is perceived by the general public. In an impressive display of cognitive dissonance, the morning that we filed the lawsuit, NYPD Police Commissioner Ray Kelly criticized the secrecy surrounding the NSA’s surveillance programs.

RK: It’s disturbing to hear reports that many Americans aren’t worried about the recent discovery of secret surveillance and harvesting of metadata. Why should we be worried about the harvesting of metadata by the government?

Metadata can be even more revealing than content.

JJ: The short answer is that metadata can be even more revealing than content. Two of my colleagues, Jay Stanley and Ben Wizner, wrote an excellent piece about exactly this. Rather than paraphrase it, I’ll just recommend it to your readers. It’s called “Why The Government Wants Your Metadata,” and it’s here.

RK: Are there any historical precedents that we can compare of past government surveillance programs that match the scale of programs like Prism and Boundless Informant or is this a first?

JJ: Obviously, the United States is not the first country to try to predict and preempt security threats with surveillance. But the scale of these programs is different in kind than anything that has been tried before—mainly because the technology available to the United States today is so much more advanced than anything that was available even, say, a decade ago. When we sued over the metadata program a couple of weeks ago, I said in an ACLU press release that the program we were challenging was “surely one of the largest surveillance efforts ever launched by a democratic government against its own citizens.” I stand by that observation.

RK: What are concrete steps you’d like to see the administration take in relation to changing course on the creation of what Edward Snowden called the “Architecture of Oppression?”

JJ: I’d like to see an end to these dragnet surveillance programs. I don’t have any issue with the government monitoring the communications of individuals who are thought to be involved in serious criminal activity, including terrorism. That kind of surveillance, though, should take place under the supervision of a court, should be based on “probable cause,” and should be directed at a specific suspect for some limited amount of time.

This piece, commissioned by Creative Time Reports, has also been published by Guernica and the ACLU’s blog.