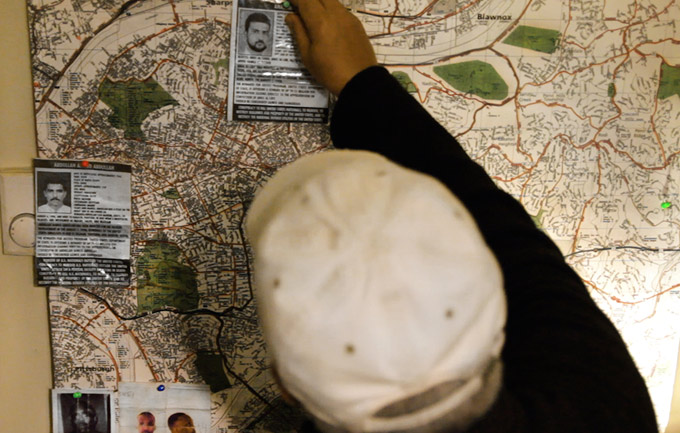

Lyric Cabral and David Felix Sutcliffe, (T)ERROR (still), 2015.

People think that catching terrorists is just a matter of finding them—but, just as often, terrorists are created by the people doing the chase.

While making our film (T)ERROR, which tracks a single counterterrorism sting operation over seven months, we realized that most people have serious misconceptions about FBI counterterrorism efforts. They assume that informants infiltrate terrorist networks and then provide the FBI with information about those networks in order to stop terrorist plots from being carried out. That’s not true in the vast majority of domestic terrorism cases.

Many informants are well-remunerated con men with criminal histories

Since 9/11, as Human Rights Watch and others have documented, the FBI has routinely used paid informants not to capture existing terrorists, but to cultivate them. Through elaborate sting operations, informants are directed to spend months—sometimes years—building relationships with targets, stoking their anger and offering ideas and incentives that encourage them to engage in terrorist activity. And the moment a target takes a decisive step forward, crossing the line from aspirational to operational, the FBI swoops in to arrest him.

The targets of FBI stings are almost exclusively Muslim men between the ages of 15 and 35. They also tend to be angry, isolated and impoverished—in other words, eager for companionship and easy to manipulate. Many of the informants are well-remunerated con men with criminal histories, whom the FBI cannot guarantee won’t coerce targets into plots in order to secure their own paychecks. The stakes are high: informants stand to make as much as $100,000 over the course of a single investigation, not to mention considerable bonuses in the case of successful convictions.

Lyric Cabral and David Felix Sutcliffe, (T)ERROR (still), 2015.

A recent example: on January 14, the FBI announced that it had interrupted an ISIS-inspired terrorist plot in the United States. Christopher Lee Cornell, a 20-year-old recent Muslim convert from Cincinnati, was allegedly plotting to attack the US Capitol with pipe bombs and gun down government officials. Cornell was arrested after purchasing two semiautomatic weapons from an Ohio gun store because the man that Cornell thought was his partner was actually an FBI informant. His plot was foiled by the FBI, after they ensured the cooperation of the store owner.

As recently as 2011, FBI counterterrorism training materials explicitly stated that most moderate Muslim Americans support terrorism

We see the same story repeated over and over: of the domestic terrorism plots interrupted by law enforcement over the past decade, all but four were initiated by an informant-provocateur acting under FBI supervision. Conveniently for the FBI, network news anchors choose to parrot FBI press releases and herald suspects’ alleged associations with radical Islam, and the steady stream of “interrupted plots” provides the government with ample evidence that the terrorist threat is ever-present and that expanded surveillance is essential to national security.

Less than a day after Cornell’s arrest, House Speaker John Boehner praised NSA spying for uncovering the plot—even though the FBI asserts that it learned of Cornell’s alleged activities through the informant. When pressed for details, Boehner refused to elaborate, saying only, “We’ll let the whole story roll out.” He added that lawmakers need to consider this particular plot when discussing amendments to the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act.

Although then-Attorney General Alberto Gonzales released guidelines governing the FBI’s use of confidential informants in 2006, there is no congressional oversight of these activities. Even though Attorney General Eric Holder recently revised federal law-enforcement guidelines to limit racial profiling, and despite evidence that the FBI engages in profiling when identifying persons of investigative interest, the FBI will be exempt from these revised guidelines in the interests of national security.

As recently as 2011, FBI counterterrorism training materials explicitly stated that most moderate Muslim Americans support terrorism and erroneously identified Islamic dress, prayer and even speaking Arabic as indicators of potential radicalization. The FBI is also no bastion of employee diversity: of the 13,766 special agents it employs, only 17 percent are “minorities,” reducing the opportunities for shifts in the bureau’s thinking on Muslims and other minorities.

Lyric Cabral and David Felix Sutcliffe, (T)ERROR (still), 2015.

The cumulative effects of FBI surveillance and entrapment in communities of color have been devastating. Mosques have reported declines in membership as individuals choose to worship at home rather than risk monitoring. Imams have expressed reluctance to discuss the complexities of jihad, a frequently misunderstood tenet of the Islamic faith, for fear that their words may be misconstrued. Many Muslims are wary of donating to Islamic charities, both domestic and foreign, for fear of raising government suspicions. And on campuses across the country, Muslim student associations have banned discussions of politics, terrorism and the “war on terror.” It is unthinkable that a diverse and vibrant American community inundated with agents provocateurs should be prevented from engaging in vigorous and open dialogue. It is also unconscionable that $1.2 billion of our tax dollars are being funneled every year into these misguided tactics.

After a recent screening of our film at a New York City mosque, a young African-American convert to Islam, sporting a brown full-body covering with matching hijab, confessed to us that she feels uncomfortable discussing aspects of her identity. She does not speak about her religious conversion in public, for fear of attracting or encouraging informants.

The stated purpose of the FBI’s counterterrorism mission is to enable Americans to go about their daily lives without fear. But in addition to imprisoning hundreds of Muslim men caught up in the FBI’s informant-led traps, the agency has actively created and encouraged a pervasive climate of fear and suspicion among Americans exercising their constitutional right to freedom of religion. In fact, the FBI’s tactics have profoundly impacted law enforcement’s ability to maintain a relationship of trust with Muslim American communities, much to the detriment to our collective national security. Authorities must rein in the informant program, and institute immediate congressional oversight, if they sincerely aim to defend the liberty and security of all Americans, regardless of race or religion.

This piece was produced in partnership with The Guardian and Sundance Institute.