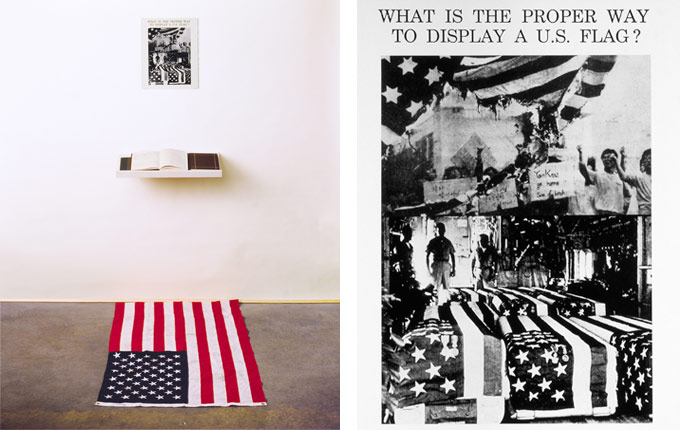

Dread Scott, On the Impossibility of Freedom in a Country Founded on Slavery and Genocide. Project produced by More Art, photographer: Mark Von Holden.

I’m not a Republican, nor a Democrat, nor an American, and got sense enough to know it. I’m one of the 22 million Black victims of the Democrats, one of the 22 million Black victims of the Republicans, and one of the 22 million Black victims of Americanism.

—Malcolm X, “The Ballot or the Bullet,” April 1964

Malcolm X was assassinated the year I was born, 1965, and the movement he led had faded by the time I started to think about much of anything more than whether my friends wanted to hang out after school. But when I was 20 years old, a friend gave me a copy of Malcolm X Speaks, and it changed my life. It was the first thing I ever read that spoke to my existence. It didn’t matter that he had been poor and that I had lawyers and professionals in my family: The Autobiography of Malcolm X recounted his uncles’ murders, and I saw the murders and life struggles of my own uncles, aunts, cousins and grandparents with a new understanding. For me—coming of age in Ronald Reagan’s America and growing up in segregated Chicago, which relegated poor and working-class Blacks to broken-down public housing—Malcolm’s speeches were liberating. I had never encountered anyone who spoke so sharply about the life of Black people in the United States and how we might get free.

Malcolm could see America without the burden of the underlying assumption that it is a force for good, and he could critique America as someone with no allegiance to it.

Malcolm looked at the conditions of the exploited and oppressed with an uncompromising view of what freedom was and how to achieve it: by any means necessary. He argued that it would take a revolution to resolve the racial problem in America. And while he held open the option that revolution could come through the ballot box, he was unequivocal in his belief that fundamental change was needed. In his famous speech “The Ballot or the Bullet,” Malcolm argued that there could not be a revolution “in which you are begging the system of exploitation to integrate you into it. Revolutions overturn systems. Revolutions destroy systems.” He studied everything from the American Revolution to the national liberation struggle in Kenya to understand how people around the world gained their independence and freedom. His grasp of the nature of oppression and his commitment to freedom from it led to his critique of the nonviolence advocated by some in the Civil Rights movement: “It is criminal to teach a man not to defend himself, when he is the constant victim of brutal attacks.”

Malcolm came to prominence in 1957, fighting against police brutality. After Johnson Hinton, a Nation of Islam member who shouted at policemen when he saw them beating another Black man in the street, was himself arrested and beaten by New York City police, Malcolm led a delegation of men from his local mosque to stand outside the police station in Harlem until he could meet with Hinton and make sure he received medical treatment. It was a defiant, courageous and unprecedented act. Negroes in 1957 were supposed to know their place and stay in it, not challenge police authority. In 1950s America, Black people faced a regime of racial segregation and discrimination, codified in Jim Crow laws, as well as the ever-present threat of lynching and Klan terror, all backed by the police and the courts. Malcolm’s actions challenged the authority of the police to do what they had done for decades—capturing, brutalizing, humiliating, harassing and murdering Black people, unquestioned.

Dread Scott, Blue Wall of Violence, 1999. An installation addressing police brutality, it was denounced as a “cop-bashing exhibition” by the New York Daily News and sparked widespread controversy when it was shown at Brooklyn’s Museum of Contemporary African Disporan Art in 2008.

After the Civil Rights and Black Power movements, the United States elected a wave of Black politicians to mayoral seats in major cities: Atlanta and Los Angeles in 1973, followed in the next decade by Washington, New Orleans, Chicago and Philadelphia. Today there is a Black president. But other than a few Black faces in high places, what has changed?

It wouldn’t be a stretch to say that Malcolm X is the grandfather of #blacklivesmatter.

Fifty years after Malcolm X was assassinated, we live in a country where the government refuses to prosecute the police when they murder Black people, even when the murders are caught on video. It is a government and legal system marked by the same racism and hypocrisy as in Malcolm’s time. Many are coming to recognize that the current criminal justice system has as little legitimacy as the one that presided over the 1955 trial of the men who murdered Emmett Till—a trial in which the police jailed Black witnesses to suppress their testimony, the judge greeted Black observers with “Hello niggers” and 12 Southern good ol’ boys, “a jury of their peers,” refused to convict the murderers. The non-indictments in Ferguson and New York drove home the fact that to this system—its police, its politicians and its courts—Black lives don’t matter.

Dread Scott, B-Ball on Rim, from the series “Ghetto,” 1993.

In the face of this situation, many have continued to advocate a gradualist path of electoral change and legislative reform, celebrating Barack Obama’s presidency. But this strategy has been a disaster, as has the Obama presidency, which has resulted in secretive new wars, drones killing whole families, the unbridled extension of mass surveillance and the absolution of torture and other war crimes. And the situation for Black people in the United States is the same hell under Obama as it has been under every other president. Black unemployment soared to 16.7 percent in the summer of 2011 and stands at 10.3 percent—more than double what it is for whites (a gap that has held steady for the last half century). Mass incarceration remains at record levels today, and Black people are imprisoned at six times the rate that whites are. Today, if you’re a Black man, there’s a one in three chance you’ll spend time in prison. Militarized police forces have been unleashed on Black people like occupying armies. We are routinely accosted and degraded, and we can be killed for selling loosies, or playing with a toy gun, or wearing a hoodie, or playing loud music, or any damn reason a cop or vigilante feels like giving.

After the acquittal of George Zimmerman in the fatal shooting of Trayvon Martin, Obama said, “In the wake of the verdict, I know those passions may be running even higher. But we are a nation of laws, and a jury has spoken.” The president’s advice after both this acquittal and the police killing of Michael Brown was to urge calm, reflection and understanding. We sure as hell shouldn’t be calm, and what we must understand is that it is open season on Black people, the courts support this and the president urges people to accept it.

Dread Scott, What Is the Proper Way to Display a U.S. Flag?, 1988.

One of the things I have loved about Malcolm since I first discovered him is his understanding that he was not an American. This was, and is, a radical stance, and it enabled him to gain clarity about the true horror that America has unleashed on Black people in the United States and people around the world. Malcolm could see America without the burden of the underlying assumption that it is a force for good, and he could critique America as someone with no allegiance to it. This perspective exploded foundational myths. He viewed America as his enemy and challenged Black people to confront this. “You wouldn’t be in this country if some enemy hadn’t kidnapped you and brought you here. On the other hand some of you think you came here on the Mayflower.” He encouraged Black people who were not, and would never become, part of America to look to freedom by other means. We are not Americans. I love this about Malcolm, and his clarity of thought is urgently needed today.

The protests in response to the murders of Michael Brown and Eric Garner are reviving some of the courage and defiance that Malcolm X inspired when he led a delegation to the Harlem police station. From Ferguson to New York, from Oakland to New Orleans, people of all races are shutting down highways, shopping malls and police stations as they protest the epidemic of unpunished police killings of Black people. Insisting that “Black lives matter,” the women who coined the phrase and the protesters who are taking it up by the thousands are drawing on one of Malcolm’s core ideas: “We declare our right on this earth…to be a human being, to be respected as a human being, to be given the rights of a human being in this society, on this earth, in this day, which we intend to bring into existence by any means necessary.” It wouldn’t be a stretch to say that Malcolm X is the grandfather of #blacklivesmatter.

Dread Scott, Imagine a World without America, 2006.

Malcolm argued that when the system is in trouble those who are most under its whip should hope that it will get in deeper trouble. The defiance in response to the non-indictments rocked this system. People were in the streets, and ferment and dissent were spreading. Now we are at a crossroads, with some urging the #blacklivesmatter movement to narrow the focus to specific legislative reforms. In the face of these appeals, which would shift the focus of the movement and rob it of its strength, let’s think about Malcolm’s understanding that we are not Americans and consider the freedom that this creates. America was founded on slavery and genocide. Rather than attempting to reform a system in which the founding documents’ conception of freedom is based on bondage, let’s work toward a world that doesn’t need cops to enforce an unjust, exploitative and racist order. Malcolm understood that this would take revolution. Through that we can bring a new country and new world into being—a world in which we all can breathe.