David Birkin, The Shadow of a Doubt, aerial banner over Liberty Island, from the project Severe Clear, 2014. Courtesy of the artist and a/political, London.

In an unprecedented move, President Obama recently apologized for a counterterrorism operation that resulted in the deaths of two Western aid workers. Warren Weinstein, a 73-year-old American, and Giovanni Lo Porto, a 37-year-old Italian, were killed when a U.S. drone attacked an al-Qaida compound in Pakistan where they were being held hostage. At a White House press conference, the president offered his “deepest apologies” on behalf of the U.S. government and promised the declassification and immediate review of the mission. His press secretary also announced that the families of the men killed would receive compensation.

This uncharacteristically contrite response reveals a glaring gap between the kind of scrutiny that surrounds certain high-profile incidents and the layers of secrecy, obfuscation and judicial quagmire that typically thwart investigations into civilian casualties. Of the thousands of undocumented deaths that have occurred since the first recorded drone strike in 2002, one still unresolved case throws the current controversy into sharp relief, both in terms of the questions it raises regarding the legal limits of execut-ive power and the total lack of accountability that it typifies.

No explanation has been provided as to why an American teenager, with no apparent involvement in terrorism, was assassinated by his own government while he ate dinner.

Abdulrahman al-Awlaki was born and raised in Colorado before moving to Yemen at age 7. In 2010 his father, Anwar, a Yemeni-American civil engineer turned cleric, was placed on a CIA kill list after being accused of serving as an al-Qaida recruiter. His grandfather, Nasser al-Awlaki, a Fulbright scholar with a PhD in agriculture from the University of Nebraska, filed a lawsuit challenging the government’s assertion that it could execute a U.S. citizen without trial, but his case was dismissed after a court ruled that he did not have standing to sue on his son’s behalf. In a New York Times op-ed, he described the events that ensued: “[Abdulrahman] left a note for his mother explaining that he missed his father and wanted to find him, and asking her to forgive him for leaving without permission. . . . . Days later, his father was targeted and killed by American drones in a northern province, hundreds of miles away. After Anwar died, Abdulrahman called us and said he was going to return home. That was the last time I heard his voice.”

Abdulrahman al-Awlaki. Courtesy of the al-Awlaki family and the ACLU

Abdulrahman was 16 years old when he died. According to his grandfather, at least five other civilians were killed in the strike, including his 17-year-old cousin. Yet to this date no apology, let alone compensation, has been offered, and no public inquiry has been launched. Nor has any explanation been provided as to why an American teenager, with no apparent involvement in terrorism, was assassinated by his own government while he ate dinner.

This March the American Civil Liberties Union filed a new disclosure lawsuit for documents detailing the circumstances under which individuals, including Americans, may be executed extrajudicially. The Fifth Amendment affirms that no person shall be “deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.” President Obama insists that individuals are targeted only when they pose “a continuing and imminent threat” and when arrest and prosecution are infeasible. But because kill lists are kept classified, verification is impossible—and in any event, the accused have no means of appeal or redress. Colleen McMahon, a federal judge who was forced to rule against her own rational judgment in an earlier case, went so far as to liken this double bind to an “Alice-in-Wonderland” paradox of “contradictory constraints and rules,” while Rosa Brooks, a former Defense Department adviser, summed up the situation in testimony at a 2013 Senate Judiciary Committee hearing: “Right now we have the Executive Branch making a claim that it has the right to kill anyone, anywhere on Earth, at any time, for secret reasons, based on secret evidence, in a secret process undertaken by unidentified officials.”

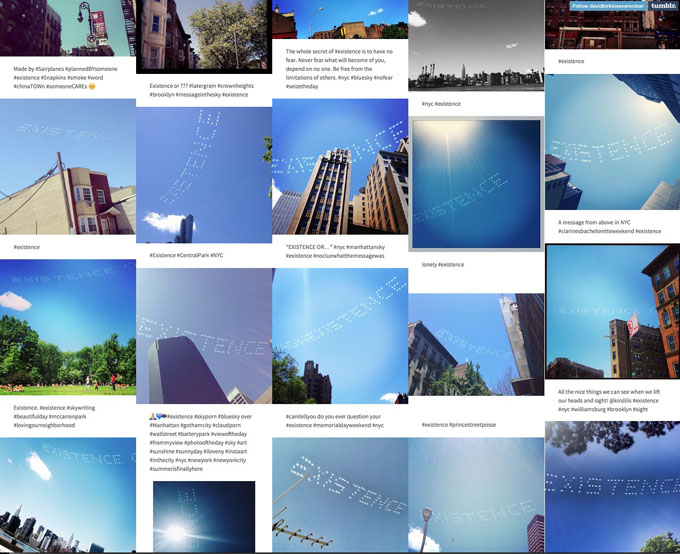

David Birkin, Existence or Nonexistence, skywriting over New York City, from the project Severe Clear, 2014. Courtesy of the artist and a/political, London.

Vocabulary helps veil the reality. Careful not to alienate the public, the Obama administration has coined the term “disposition matrix” to describe its database of terrorism targets, adding to a veritable lexicon of lethal lingo that includes such dispassionate terms of art as “painting a target,” “servicing a target,” “neutralizing a threat,” “extraordinary rendition,” “collateral damage” and “blue on white.” What’s more, until very recently, when two appeals courts rejected the CIA’s arguments, the agency had never even acknowledged its drone program officially. Instead, requests filed by the ACLU under the Freedom of Information Act have been met with a notoriously equivocal boilerplate reply: “The CIA can neither confirm nor deny the existence or nonexistence of records responsive to your request.”

Named after a Cold War–era ship, the “Glomar response” is a Dear John letter to accountability: a linguistic somersault that—by saying, in the most precise terms, nothing—spins news of rejection into a kind of esoteric existential rhetoric. In response to this Kafkaesque specimen of legalese, I staged a public performance on Memorial Day weekend last year, skywriting the words “EXISTENCE OR NONEXISTENCE” over New York City in synchronized bursts of white smoke. Viewing it from below, some passersby construed the message as a theological proposition or a reference to Hamlet’s “To be or not to be” soliloquy, while others assumed it to be a meditation on the existence of UFOs: a rather apt reaction given the proliferation of drones—or UAVs (Unmanned Aerial Vehicles) in military parlance—over the past decade. Images of the event spread rapidly across social media, and the varied and often fantastical interpretations underscored the nebulous nature of the government’s reply. Then, a little over a week later, in what seemed an unlikely coincidence, the CIA officially joined Twitter with its maiden message: “We can neither confirm nor deny that this is our first tweet.”

The @CIA’s first tweet.

Orwell had a term for this type of obtuse logic. He called it doublethink: “To know and not to know, to be conscious of complete truthfulness while telling carefully constructed lies.” One of the key criticisms of the drone program is the contorted manner in which casualties are counted, following the government’s redefining of the term “combatant” to include “all military-age males in a strike zone . . . unless there is explicit intelligence posthumously proving them innocent.” Shamelessly expedient, and flagrant in its contravention of international law, this tautological reasoning mirrors a medieval trial by ordeal: a judicium Dei (judgment by God), in which death denotes guilt, while a miraculous intervention offers the only hope of exculpation. It also helps account for the extraordinarily low figures for civilian fatalities—a point underscored by the government’s recent admission, after months of denials, that an airstrike in Syria “likely led” to the deaths of two children.

In the face of overwhelming evidence of innocent deaths, government officials continue to promote a vision of “surgical precision” in which drones save lives.

The Bureau of Investigative Journalism puts the total number of drone victims at upwards of 3,000, while Reprieve has calculated that in pursuit of 41 men, a staggering 1,147 people were killed, 149 of whom were children. Many of these casualties have resulted from a reliance on so-called signature strikes, in which individuals are targeted on the basis of ostensibly suspicious patterns of movement alone rather than any form of positive identification. These speculative attacks may then be followed up with a subsequent strike—or double tap, to use the euphemistic jargon—on those coming to aid the initial victims, in clear violation of the Geneva Convention. Chillingly, such decisions are reached by monitoring communications metadata, as former director of the CIA and NSA General Michael Hayden confirmed with remarkable bluntness: “We kill people based on metadata.” Yet despite this, and in the face of overwhelming evidence of innocent deaths, government officials continue to promote a vision of “surgical precision” in which drones save lives.

Such claims are plausible only if one subscribes to the administration’s obfuscatory terms of engagement. The New York Times reports that counterterrorism officials regard those found in an area of known terrorist activity as “probably up to no good,” while Harvard law professor Alan Dershowitz, who made headlines advocating for the legalization of torture under warrant, has proposed an insidious new phrase, “the continuum of civilianality,” reaching the truly Orwellian conclusion that “Every civilian death is a tragedy, but some are more tragic than others.” As with the universal prohibition on torture, and its steady corrosion by the term “enhanced interrogation,” here we see language evacuated of meaning as a way of opening cracks in people’s moral positions regarding even the most inviolable principles.

Words matter. Legal terms matter. “Less than innocent” is not a charge, and guilt by association is no substitute for evidence. Last Veterans Day, as a follow-up to my skywriting project, I commissioned a plane to circle the Statue of Liberty’s torch towing a banner that read “THE SHADOW OF A DOUBT.” The phrase refers to the highest burden of proof a court can demand. Together with its more practicable counterpart, “beyond a reasonable doubt,” it reflects a recognition in the justice system that criminal trials require an exceptional degree of certainty, because the verdict may result in the deprivation of someone’s liberty, or even life.

Following the Western aid workers’ deaths, President Obama praised the transparency of his administration: “The Weinstein and Lo Porto families deserve to know the truth.” Surely Abdulrahman al-Awlaki’s family—along with the thousands of other Yemeni, Somali, Pakistani, Iraqi, Libyan and Afghan families—deserves the same.

Existence or Nonexistence, 2014. Skywriting images uploaded to social media from across New York City.