Mladen Miljanović , I Serve Art Project, photo documentation of performance, Day 274, Ex-military base Vrbas, 2006.

The first time I saw artist Mladen Miljanović’s work was in a park in central Budapest where he was set to reprise his sonorous performance piece A Sweet Symphony of Absurdity for the OFF Biennale. The rain that morning was unforgiving, which meant Miljanović’s presentation—which was comprised of a handful of musicians each playing their favorite piece of music at the same time—was moved under a concrete overhang. As the rain flipped between a heavy patter to a drizzle, a potpourri of sounds emerged. The assortment forced the viewer to home in on the expressions of those that were playing them, watch how they related to the music they loved most. A few months later, with a generous grant from the Trust for Mutual Understanding, an organization that supports creative collaborative exchange with Russia and Central and Eastern Europe, I had a chance to visit Miljanović in his hometown of Banja Luka, five hours from Sarajevo, and talk with him about his practice.

Creative Time Reports (Marisa Mazria Katz, editor):You have a fascinating trajectory: you went from being a soldier in the Bosnian army to becoming an artist—all within just a few years of the ’90s war. How would you describe this journey and how did it influence your work as an art practitioner?

Mladen Miljanović: When I finished my obligatory military service, I had the option to stay on as a professional soldier. But I really wanted to leave, which, let’s say, was an unconscious way to resist the military. As it happened, the art school I later attended was moved into the former military base where I had served, a base originally established by the Austro-Hungarian Empire. I couldn’t resist dealing with it in my own art, especially because of the many negative connotations that military activities have had here in the region from the First World War until the last war in the ’90s. So I decided to confront it in my artwork.

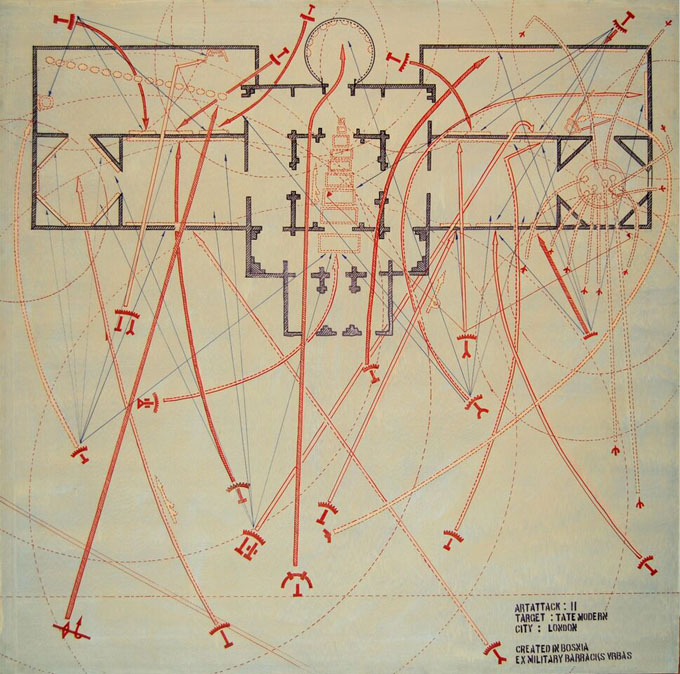

CTR: Your project I Serve Art really dealt with this military space, perhaps in many ways more physically than other projects of yours, particularly because it took place over nine months on the base. In fact, you never left the base during the entire duration of the project. How would you characterize I Serve Art and the interaction it had with this space?

MM: I was actually fascinated by two different paths to that very space. The first path was the personal one, the experience I had there during my military service. The nine-month period I spent living on the base for I Serve Art was the exact same amount of time I had served in the military. When I returned to the base to study as an artist, I was able to be free, to speak about everything, which is completely, diametrically opposite to being in the military.

Mladen Miljanović, Тhe Garden of Delights, engraved drawing on granite, Pavilion BiH 55th Venice Biennale, 2013. Photo by Drago Vejnovic.

The other path I had been fascinated by and, let’s say, provoked by was actually the 100-year military legacy of the space. I observe it as a generational problem. I see it as a century of generations being militarized in that space. This path, it’s more, let’s say, objective.

At one point the I Serve Art project employed the strategy of using art as a tool to suggest that society move in a positive direction. At another point it was using art as a “tool of power,” showing how art can document and also transform society’s problems.

CTR: Where did you get the stamina to produce such a labor-intensive project?

I think that art is a decision. Actually, when you decide to do something, that’s half of the work. The other part is just realization.

MM: I think that art is a decision. Actually, when you decide to do something, that’s half of the work. The other part is just realization. But in this case the decision to spend 274 days on the former military base doing the project could have been seen as very easy, with the realization part actually being extremely hard. So I knew that at some point I would have a crisis, mostly psychological, and would possibly want to quit and stop the performance. But then I decided to employ a military strategy, which was to remain busy all the time.

The main documentation of the performance was the photo I took each day at a different location in the military barracks. Each image was taken with a tripod and a self-timer. In each photo I stood ten steps in front of the camera and held myself straight, military straight. These full-body images and landscapes were key to mapping the space. The auxiliary website, which I launched before the project, was used to map the transition of the space. These daily photos were then posted on the project website. I saw them as a kind of contamination of the space. Nobody knew what was inside. That’s because when it was used by the military, it was forbidden to go inside or to take pictures of it. It was a restricted area, completely closed to the public. That was just one of the works realized during those nine months.

CTR: With the 20th anniversary of the Dayton Accords this year, I wanted to talk about your groundbreaking project Happening Balkana. The project was staged as an art workshop for people with disabilities, many of whom lost limbs in the war. Most importantly, all three of Bosnia and Herzegovina’s ethnicities were represented. It was one of the few art projects that touched on the postwar state in a way that it seemed a lot of people weren’t willing to risk. What pushed you to do something that was practically impossible to fund within your own country, and how has it shaped the contours of your art practice today?

MM: Happening Balkana was maybe my most socially risky project, risky because I participated not just as an artist. In fact, I wasn’t important there. The most important people were the participants who were traumatized by the war, people who were victims of trauma after the war. I think in that period everyone identified with them. The war didn’t stop with the peace agreement. Only guns stopped shooting. And trauma was felt not just by the people on the front lines but also by the families. At that time, I remember, people were not so conscious of that. Organized efforts for ethnic resocialization were not well organized at all. There were many organizations that were kind of throwing money at projects and not really focusing on how they could affect or help society. As a volunteer in the NGO Amputee Association (Udruženje Amputiraca, or UDAS), I saw many traumatized people, and I saw the possibility of using art as a tool. I saw it having a positive effect and a real power in society. This is why I decided to gather the three sensitive ethnic groups—Muslims, Croats and Serbs—into a space for about four days to create sculptures, photographs and paintings. Everybody was very skeptical. I couldn’t get any funding here on a local level. The only organization that helped was the LSN, Landmine Survivors Network, which was a network of the Canadian government, along with some funds from Washington, D.C.

Mladen Miljanović. Attack: TATE, from I Serve Art, 2007.

CTR: What kind of reception did the project get?

MM: Once the project was done, we made an exhibition of the work produced. We had a lot of news media coverage as well as high attendance records. The reaction spurred many people to think about how the participants, who were working together and creating something, were true models of cooperation. One year later, Happening Balkana received an award from the United Nations. In its aftermath you could see everybody wanting to fund projects like this on a local level.

CTR: Did this experience transform your understanding of how artists function within society?

MM: I think the position of artists is to always try and push people’s boundaries. And I see the role of art as important in post-conflict societies. It acts as an alarm when something goes wrong. It is not only about creating beautiful objects but also about articulating the problems and making them into artifacts, and that’s the power of art.

Before I entered the art academy, I had a job manually engraving tombstones in a factory. In this profession I saw many people who wanted me to engrave their wishes on tombstones—in other words, to carve images of their unrealized dreams.

CTR: You have been described as one of the artists who helped to define the local postwar art scene in Bosnia-Herzegovina. Were you comfortable with that designation? And how would you say the postwar art scene has taken shape over the past 20 years?

MM: Around 2004 and 2005 this term postwar was everywhere. Most of the artists who were present from 1997 to 2005 were associated with this term. I noticed that when the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan began, people stopped using it. Still, I see this term as very romanticized and even a little bit like something to hide behind, which gives you an excuse to do anything. Still, I think the generation that experienced the war can really be identified as a postwar generation of artists—that one cannot remove themselves from the context of where they live, work and create.

CTR: You talk of yourself as a kind of artist-anthropologist, and I wanted to understand what that might mean.

MM: I think that the term anthropology is often used in a sphere of history, but I also think that the term can be observed in the context of an artist, as someone who is dealing with the anthropology of a society, either temporary anthropology or even anthropology of the future. In this case the phrase “anthropology of the future” acts as a paradox. Artists can do work that is a kind of research, which can lead to deep, concrete developments in the future.

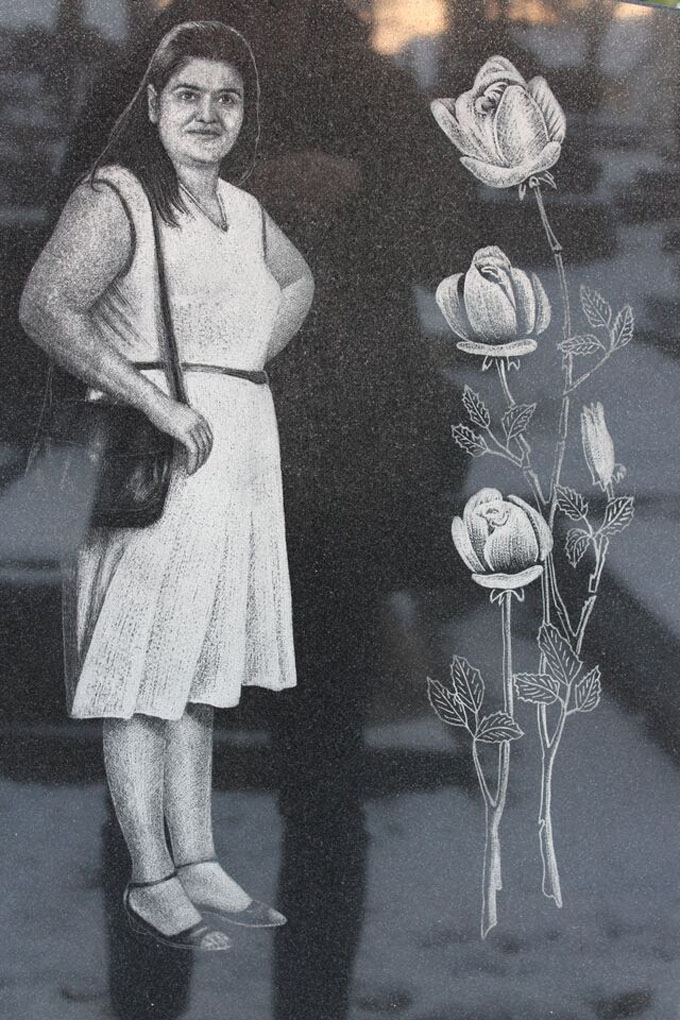

An example of this was The Garden of Delights, the project I created for the Bosnia and Herzegovina Pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 2013. As an artist, I researched, collected, archived and dug into the motives and wishes of the people featured. All of this went into one collection, and its final form was a triptych. The Garden of Delights analyzed indulgences, pleasures and desires in our society in this era. This work is not a work of fiction; it is made of fragments that are grounded in reality.

Mladen Miljanović, Тhe Garden of Delights, collected motifs, engraved drawing on granite, 2013. Photo by the artist.

Before I entered the art academy, I had a job manually engraving tombstones in a factory. In this profession I saw many people who wanted me to engrave their wishes on tombstones—in other words, to carve images of their unrealized dreams. During that time I met a woman who asked me to create a tombstone for her husband, who had died in a car accident. So she brought two pictures, one of her husband and one of her, because she wanted her tombstone to be next to his. His picture showed him standing next to a car, and her picture showed her in a skirt. I said to her, “Sorry, but isn’t it a little bit morbid to carve this image since your husband died in a car accident? Do you really want the car next to him?” She said, “Yes, of course, you need to draw the car next to him. He really loved that car. He was washing that car every day. He saved up money to buy that car.”

Over the next two days I made a sketch. When she came over to approve the image, my boss was standing there, and I detected that she was uncomfortable talking to me about something. When he left, I asked her to tell me what the problem was. She told me that she felt that her husband was drawn perfectly, but for her own picture she asked if I could make the skirt shorter. The skirt in the picture was down below her knees, and she wanted it above the knees. I said, “No problem, I can make you naked if you want.”

Ten years later I was thinking about the length of her skirt but not in a perverted way. The shortened skirt was her own wish for what she couldn’t be in this world, because of either morals or traditions. Her eternal wish was to be remembered as what she wanted to be.

It is in those moments that you discover someone’s imaginary creation of a world that doesn’t exist but one that they want to live in.

CTR: Do you think it’s possible to be overwhelmed by history?

MM: Yes, especially here. Politics and the media are bombing the social and public spheres with history. The result is that you not only ignore the present but you also do not have any kind of influence over the future. That’s why I think that the moment when art or an artist starts to intervene directly into the public, into the current reality, and moderate it even a little bit, it means you have the possibility to change something right now. By creating artifacts, you are problematizing something that is still in the past.

At the beginning of my career, you can see in works like I Serve Art that I was dealing a lot with my own past as well as this society’s. And I knew that first one needs to move on from the past by sublimating one’s own experience. And then one needs to arrive at the current moment in order to deal in reality. I try to intervene directly into life—this way art becomes life, and vice versa. But I think the crucial moment of my art practice will be to intervene in the future, to try somehow to moderate reality, and that moderation could actually alter the future.

On that level, art is the same as a science, because both science and art are interested in the impossible—pushing borders and even venturing into the unknown. When everybody understands your work, you don’t change anything. An artist doesn’t need to be understood; that’s actually avant-garde. In the French language avant-garde means the troops who are ahead of the other ones. And once again, it seems, we have come back to the military.

Mladen Milijanović, Happening Balkana, Dragan Popovic and Sabahudin Avdic, photo with permission, 2005.