Vintage advertisements, vernacular photographs, old magazines and postcards that appear to have outlived their relevance are the images that I am most inspired by. Though these things are often dismissed, I believe these forms of ephemera and material culture should be cherished, mined and studied with the same rigor as any historical document. Unwittingly they provide insight into a society’s hopes and dreams in a particular historical moment while simultaneously functioning as a bridge and throughway to future moments. Seemingly insignificant, they act as bellwethers, marking the evolution of popular thought through trends in advertising and the popularity of certain trends and tropes.

According to Merriam-Webster, an advertisement is “something (such as a short film or a written notice) that is shown or presented to the public to help sell a product or to make an announcement.” If we read this literally, any image or sequence of images produced for public notice can be seen as an ad, because such images generally function to support or “sell” the status quo. By investigating these images as artifacts, might we reveal counter-narratives that inspire us to reimagine their relationship to the present moment?

In The Society of the Spectacle, Guy Debord writes, “The spectacle is not a collection of images; it is a social relation between people that is mediated by images.” He continues, “The spectacle cannot be understood as a mere visual deception produced by mass-media technologies. It is a worldview that has actually been materialized.” In The Medium Is the Massage, Marshall McLuhan writes, “The medium is the massage. Any understanding of social and cultural change is impossible without a knowledge of the way media work as environments.” Using these writings as cues, I investigate the power of media images, particularly advertisements, to support or subvert misleading “grand narratives” about history and the present moment.

Dehumanization and violence were the common media response to the anxiety that people’s demands for their rights produced, no matter who was making the demands.

One hundred years ago D. W. Griffith’s epic film The Birth of a Nation was released. It continues to be seen as a triumph of storytelling, even as it has also been widely acknowledged that Griffith’s story was not only false and manipulative but also actively hateful and damaging. The film decried an imaginary era when empowered “black” (male) voters rigged elections and exploited power to disenfranchise “white” (male) voters. One of the climactic moments of the film depicts a “black” man lusting after a vulnerable “white” woman, literally chasing her to death. At the height of the Jim Crow era, with African-Americans (primarily men) being lynched because of anxieties about miscegenation and voting, the activist and educator Mary McLeod Bethune, arguing for the equal rights and education of “black” women, stated, “The true worth of a race must be measured by the character of its womanhood.” While “white” men lynched “black” men in order to “protect” the virtue of “white” women, and “white” suffragettes agitated for their right to vote, “black” women were excluded entirely, worthy neither of protection nor the vote. Postcards from that era depict horrible caricatures of both suffragettes and African Americans, male and female. Dehumanization and violence were the common media response to the anxiety that people’s demands for their rights produced, no matter who was making the demands.

The undeniable connection between the mass production of images used to suppress, distort and trivialize the lives and ambitions of people of African descent and “white” women suggests a conspicuous strategy by media makers to affect the social order. Simultaneously, similar images were produced of recent immigrants from Europe and Asia. It can be assumed that the expectation was that the presence of certain people in public life would always be suspect or novel. The irony is that the majority of the population of the United States at any given time has always been a combination of women, people of African descent and recent immigrants. Given this truth, one might assume that a coalition of empowered individuals devoted to setting the record straight and fighting for liberty and justice for all might have emerged. Instead the promise of coalition was set against itself, via these images and other devices, which functioned, then and now, as subversive tools to divide and conquer. Creating a perception of otherness allowed generic perceptions of different groups to solidify in the cultural psyche of members of each group, the control perspective typically defined by “white” men.

I see visual culture as a battlefield in the struggle to make all lives matter in the truest sense.

While women like Bethune fought for human rights, most “white” suffragettes fought for the right to vote, ignoring the disenfranchised “black” women who could have been their greatest allies. “Black” men fought for their rights, ignoring the liberation struggles of women and recent immigrants. In their moves toward assimilation, most recent immigrant populations have rarely or only temporarily aligned themselves with other movements. In almost all cases the indigenous population was not considered.

The vast majority of these issues came to a head for a brief moment in the multicultural movement of the 1980s and 1990s but was followed by a backlash to “political correctness.” The inherent intersectionality of these various positions is undermined by the black-lives-matter versus all-lives-matter debates, which position things as either/or instead of both/and. “Black” lives are all lives because the value of human life is indivisible, unquantifiable and indistinguishable. The only thing that obscures this existential truth is the mythology of distinct human races.

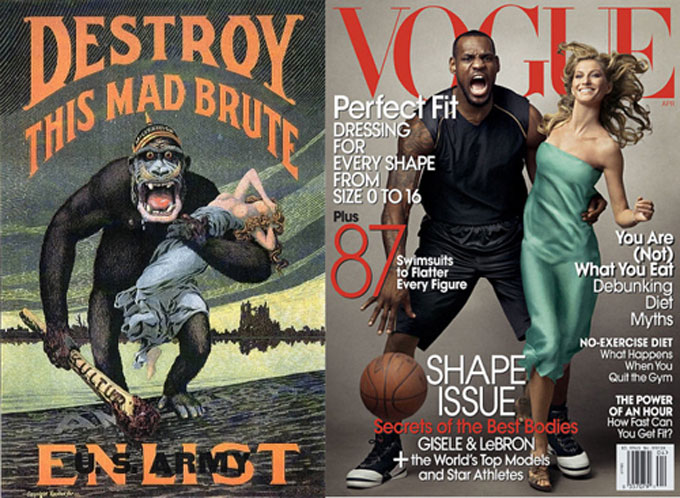

In this 2008 Vogue cover, basketball star Lebron James and supermodel Giselle Bundchen are proxies for presidential candidates Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton.

I see visual culture as a battlefield in the struggle to make all lives matter in the truest sense. Over the past 100 years, from the time when most women didn’t have the right to vote and most “black” men were implored not to do so, there have been incredible strides along with incredible setbacks. Each step has been fueled, measured and recorded by media images. A century after the release of The Birth of a Nation, an intersectional coalition put an African American family in the White House, and a “white” woman is following suit in her bid as the front-runner in the election to replace them. A more culturally diverse and aware generation of media makers is rewriting and complicating once entrenched narratives about who we are and what we can be and where we belong. The country seems to be on the precipice of being born again, and history is being retold as histories. New stories seem to strike different tones, but the narrative too often leads to similar conclusions. While there is clear progress in the visual landscape, the dividends paid to the new investors still appear to be far-off, as class divides, mass incarceration and intra-community and police violence persist.

While millions protest across the country and across the globe, the movements still rarely align. Collectively, the Occupy, immigrant rights, Black Lives Matter, women’s rights, Arab Spring, and LGBTIQ movements are steadily making the claim that all lives matter. The revolution has been televised. Consumerism and various forms of mass distraction inundate citizens into lethargy and skepticism. They have also made once unimaginable shifts in cultural consciousness commonplace. Media have been coopted by the masses in ways never seen before and on a scale unmatched. There is no longer a grand narrative or singular gaze controlling and patrolling cultural and class borders. It is increasingly difficult for governments and corporations to do business as usual, but it is also increasingly difficult to sift through the images and distill a pathology. With the rapid changes of the past decade, it hard to imagine that the things we celebrate as progressive will likely seem repressive or at best passé 100 years from now. The road to progress is always under construction.