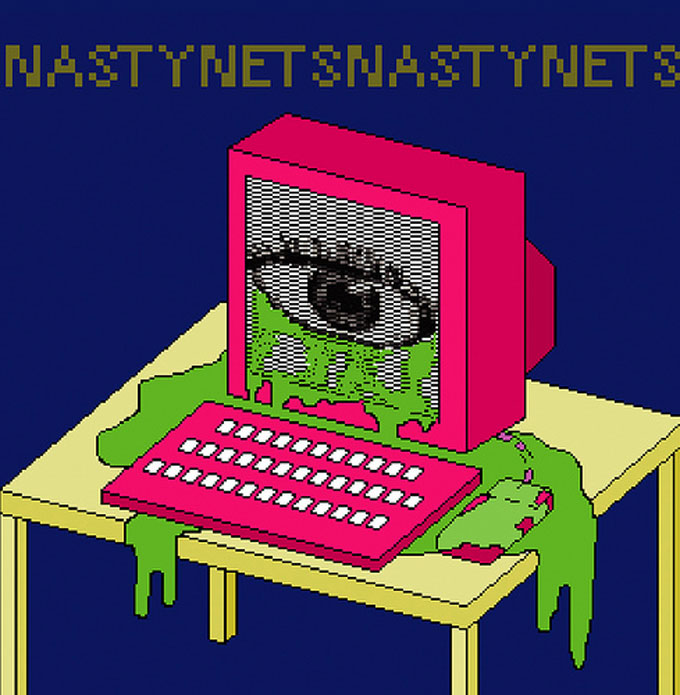

Nasty Nets DVD cover, 2008.

Concerns over “information overload” are the growing pains of the so-called Information Age. Network culture now permeates offline life. We have higher-than-ever expectations about being available, being up-to-date, having clever opinions and cute pictures to broadcast. There are frequent studies on the effects that general “decision fatigue” has on our psyche.

But this is a fake problem, confusing bombardment with addiction.

Attention is a finite resource facing an infinite internet. Previously scribes, readers and librarians carefully selected specific texts with which to engage. Now, when anyone with a keyboard and network connection can be a “published author,” we have to choose which texts (or sites, slideshows or Twitter feeds) deserve our attention.

This sort of confused reaction to technological paradigm shifts isn’t new.

And we’re still in that kid-in-a-candy-store phase when we want it all and even challenge ourselves to consume it all, when really it’s time to distinguish between gummy cokes and malt balls, perhaps forgoing candy altogether and opting for vegetables. Just because the data is there to be consumed doesn’t mean we have to partake.

This sort of confused reaction to technological paradigm shifts isn’t new. Historians have noted that electricity, railroads, billboards and newspapers were all thought to overwhelm our body clocks and fry our minds when they first came on the scene. Thankfully it is much easier to close our eyes and ears to the internet than to billboards or ambient radio transmissions. Many of us simply lack the confidence to do so.

I currently follow zero people on Instagram. Some friends find this rude, but if I want to see what my friends are up to, I seek them (or their online personages) out directly. And meanwhile I save myself scroll time and FOMO: fear of missing out.

Please don’t mistake me for some kind of digital temperance fanatic. I know all too well the feeling of loving the web like your life depends on it. In 2006 some friends and I started a net-art blog called Nasty Nets, one of the first online places where artists alchemized the heap of content the net has to offer. Within a few years I nervously took a web addiction test and swept the board, answering yesses to all the questions. My all-night gif-hoarding sessions and social-bookmark scrolling continued nearly unabated until something happened that truly made me feel powerless.

I was cyberstalked by one of my former graduate students, who impersonated me on Twitter using my name and image and a bio along the lines of “I’m Marisa Olson and I’m a slut.” He befriended hundreds of people who thought it was my account (including an ex) and posted countless derogatory, embarrassing comments—all while I was sleeping. I could not control what happened online when I was asleep.

Many of us fear the consequences of unplugging—not feeling like the first to know something, not being in on a joke, missing a magical business offer or the newest email.

After racing to get the defamatory account taken down and delete the dozens of harsh blog comments he’d made about me (thank you, Google Alerts!), I paused to consider what I could have done differently. I realized that this was a less-is-more situation. If I was going to be less vulnerable to such attacks or to the general pitfalls of digital disappointment, the answer was simple: I needed to be less invested in the web and live less exclusively online. If I can do it, everyone else can, too.

Many of us fear the consequences of unplugging—not feeling like the first to know something, not being in on a joke, missing a magical business offer or the newest email. But on the rare occasions when we do unplug, we often find that time passes more slowly; a little while offline brings a lot to our lives. We may not be able to reply to a message immediately, but very seldom does the sky fall.

This piece, commissioned by Creative Time Reports, has also been published in The Guardian.