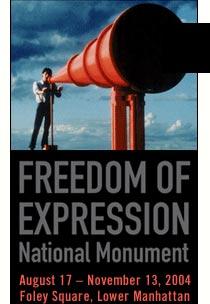

A modern day soapbox, Freedom entices passersby to climb its sloping ramp and embrace the megaphone to voice their thoughts, poetry, grievances, and hopes. Offering a public forum for dialogue on the dynamics of free speech, power and powerlessness, and a multiplicity of social and cultural concerns, the artwork directly addresses public frustration over getting its voice heard. Both celebratory and ironic, Freedom evokes the struggle involved in making change, while reflecting the public’s desire to break through mass media and partisan politics where individual voices tend to diminish.

Freedom was originally installed in 1984 for Art on the Beach (1978-1985), Creative Time’s annual program that featured collaborations between architects, performers, and visual artists on the Battery Park City Landfill created by the construction of the World Trade Center. The piece captured the imagination and quickly became one of New York’s most cherished artworks. For one memorable summer, thousands seized the megaphone on the windswept beach to vent, sing, rage, and recite poetry. Freedom brought contemporary issues to the fore — the AIDS pandemic, homelessness, human rights, economic disparity, the environment — and asserted the importance of standing by our right to express ourselves.

Although a great deal has changed since then, the artists point out that much has stayed the same. The range of issues for the public to weigh in on — from globalization to widening wealth inequality to the War on Terrorism — has never been as vast. Nor have the stakes been as high. As presidential campaigning got underway last year, Creative Time recognized Freedom of Expression National Monument’s continued relevance. We weren’t the only ones. Architecture critic Herbert Muschamp proposed in The New York Times last year that Freedom be rebuilt at Ground Zero. He wrote, “The need for such a public platform has never been greater than it is now.” (NYT, 8/31/03)

In both form and experience, Freedom disarms and empowers. Drawing on the iconography of Soviet agit-prop, the artists designed Freedom as a playful and approachable object. The structure, made of plywood, steel, and rolled sheet metal, is painted a bright red that radiates from a distance. By climbing the twenty-one foot long ramp to the six-foot tall platform, the visitor is elevated to a position of importance and power. Once there, the speaker embraces, and is simultaneously overwhelmed by, the exaggerated megaphone that sends his or her message to the world.

Freedom also challenges our assumptions about the role of civic architecture, which the artists gesture towards by naming the artwork a “national monument.” Unlike Washington D.C.’s monuments, this temporary intervention is constructed on a human scale with affordable materials. Rather than venerate great men and enduring institutions, Freedom honors the ordinary and everyday.

Freedom will resonate just as strongly this election year as it did two decades ago by drawing our attention to the ways in which first amendment rights intersect with our daily lives. Its proximity to courthouses, for example, alludes to how easily a privilege that we take for granted can be ensnared in a complex legal web like the Patriot Act. Furthermore, Freedom reclaims Foley Square as a public space in the classic sense – a town square where ideas can be openly shared and debated.