The surf gently laps against a line of eroded beams leading into the water, a picturesque view of natural decay. Behind these beams, though, is a shattered landscape of climate disaster that is anything but natural. The beach is several hundred yards from Beach 100 Street in Far Rockaway, one node in the network of emergency-relief sites where Occupy Sandy has been operating for the past three weeks. The physical and social destruction the hurricane wrought is difficult to represent, as is the relief effort. Things change rapidly on the ground. The landscape mutates by the hour, even as the emergency remains acute. What does it mean to see Sandy? Among other things, it means seeing beyond the State.

After the storm struck, people did not wait for the State. They declared their own emergency. While the State and the traditional relief agencies sat around and waited for orders from on high, the People stepped in. Mobilizing supplies and volunteers, they collaborated with folks on the ground whose lives were in danger from hunger, darkness, and exposure to the elements. This has not been a humanitarian operation. It is not about charity. We are seeing the creation of autonomous zones for community and solidarity, not camps for managing the lives of powerless victims.

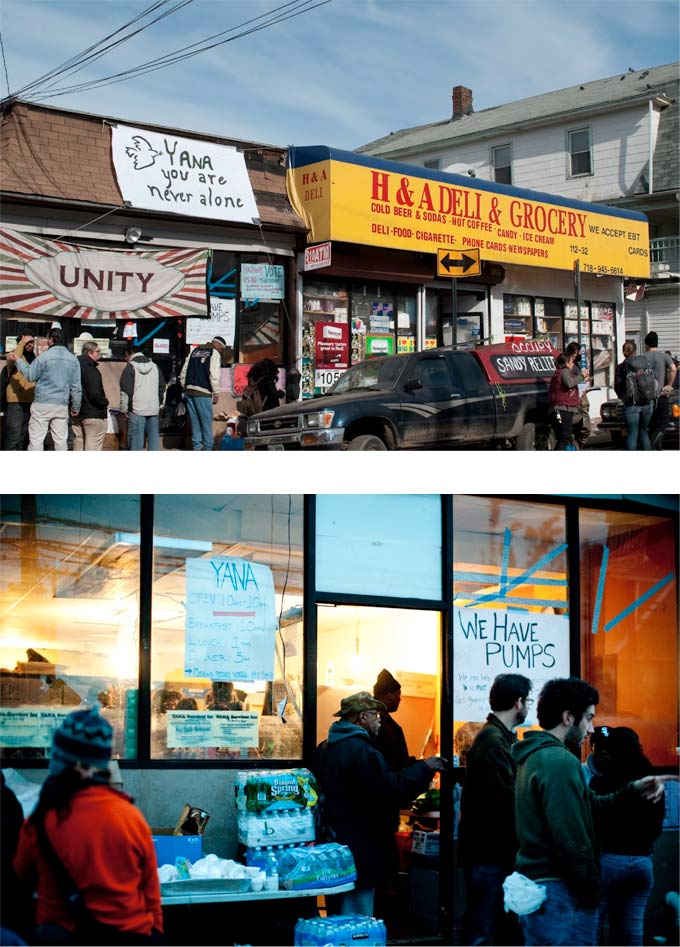

Yana, an Occupy Sandy site at Beach 113 Street and Rockaway Beach Boulevard, November 2012. Photos by MTL.

Occupy Sandy’s actions are autonomous, but this does not mean they are indifferent or hostile to the State. People are simply stepping into the void to do things for themselves as the clock ticks and winter storms approach. The line between government and governed is being blurred; people are commandeering state infrastructure, equipment and personnel. In the Rockaways, an MTA bus has been borrowed to set up a relief center, and National Guard troops stood in line to unload trucks at an Occupy Sandy hub. The mayor and FEMA congratulated Occupy on a job well done, if only to insist they can take over the emergency management efforts from here. After a year of brutality and suppression, city authorities are starting to “recognize” Occupy. The question, though, is not whether they recognize Occupy, but whether Occupy recognizes them.

Occupy Sandy volunteers unload an MTA bush, November 2012. Photos by MTL.

The State is temporarily disarmed, and a different kind of power is being practiced. “The People’s Emergency,” as some are calling it, could be a real emergency for the State because the people on the ground intend to sustain their work beyond the immediate crisis. They are doing something different from the disaster management of the State and traditional relief organizations. Even as they respond to the short-term crisis, they are building power from below and establishing networks of intensive care and mutual aid for the long term. Self-organized legal aid clinics, reconstruction hubs and free stores are being set up around the city. All the while, the State struggles with what to do about Occupy and its new friends on the ground. Co-opt? Collaborate? Suppress? Something in between?

As Occupy flourishes with its community-based allies, other forces are mobilizing. Disaster capitalists are swooping in, seeing an opportunity to foment a debt-based recovery for communities already suffering from predatory lending of all sorts. The specter of gentrification already loomed large over the Rockaways before the disaster. By a perverse historical twist, the region may find itself all the more in danger of elite redevelopment now that it is in the headlines due to the suffering its people have endured. Debt and disaster are intimately connected, and organizers are integrating this fact into their analysis as they imagine what a People’s Reconstruction might look like.

Meanwhile, race haunts everything in this process. We know that low-income communities of color are the hardest hit by environmental and economic disasters, from the subprime mortgage crisis to Hurricane Sandy. We know that communities of color are often living in the most precarious conditions, but also, that they have longstanding traditions of resistance and mutual support, which they activate in times of crisis. Occupy Sandy works in partnership with these networks, such as the Rockaway Youth Task Force. It is cautious about taking credit or receiving attention when its work is based on relationships with local communities and organizations that know the people and the terrain.

In recent weeks, thousands of volunteers—mostly white, young, and privileged—have fanned out to disaster sites across the city, with the Rockaways becoming a kind of cause célèbre. Even as relief efforts are undertaken in the name of “solidarity, not charity,” the racial facts remain: these are mostly white people, helping mostly brown people, often facilitated by Occupy organizers of color. This is not a bad thing. But it should not go unexamined, if only because it represents a remarkable chance for the long-term radicalization and education of privileged people. It will be a missed opportunity if these thousands of volunteers go through such an experience in the spirit of a one-time field trip or a pilgrimage of white guilt. The default is to donate some time, some energy, maybe some clothes and some food, and then to feel better about oneself.

What is the alternative? Who knows, but asking the question is the first step. Moving from relief to reconstruction cannot succeed without help, but we need to redefine what helping means. This process will be disorienting and difficult, not a mere walk on the beach by disaster tourists, who are always eager to find the latest frontier of urban authenticity.