Following photography’s invention in the mid-1800s, colonizers and travelers photographed and disseminated images that portrayed Cambodia as an exotic land. It was only at the outset of the Independence years (1953–70) that the country began to record itself, but this practice was interrupted, and its archive mostly destroyed, by war. Concerned by the lack of physical documentation of the stories, traits and monuments specific to the country’s past and present, Cambodian photographers and artists are devising new ways of showing and telling. Below we share a selection of photographic portraiture—both of self and community—that hints at a variety of social experiences in today’s rapidly changing Cambodia.

Lim Sokchanlina, born 1987

Lim Sokchanlina, My Motorbike and Me, 2008. Courtesy of the artist.

Lim Sokchanlina, My Motorbike and Me, 2008. Courtesy of the artist.

In 2006, when Suzuki introduced the automatic motorbike “Smash Revolution” to the market in Cambodia—a nation with one of the youngest populations in the world—it advertised, and became synonymous with, new forms of freedom. Lim Sokhanlina, then 19, observed how longstanding ideas of fashion, mobility, leisure and dating were transformed: a new generation cruised the streets on Japanese motorcycles, wearing trendy clothing imported from Seoul. In this series of critical and humorous self-portraits, Lim and his motorbike team up as protagonists, taking center stage to hint at some of the problems associated with new forms of globalization.

Neak Sophal, born 1989

Neak Sophal, No Rice for Pot, 2012. Courtesy of the artist.

Neak Sophal, No Rice for Pot, 2012. Courtesy of the artist.

To create No Rice for Pot, Neak Sophal collaborated with women from her home village in Takeo province, where much of her family still lives. Titled after a colloquial complaint frequently voiced by Cambodian women, the series of portraits speak to the woman’s primary responsibility and vital role within most Cambodian families: nourishment. Although the Cambodian economy is growing steadily, one in three people currently live on 61 U.S. cents per day. Neak thus honors the challenge women face in providing for not only their families but also society as a whole, today and throughout history.

Sovan Philong, born 1985

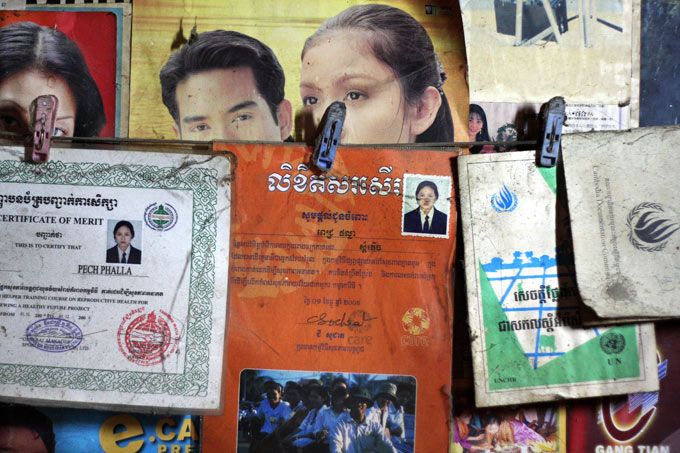

Sovan Philong, The People of the Old Church Building Part 2, 2009. Courtesy of the artist and Asia Motion.

Sovan Philong, The People of the Old Church Building Part 2, 2009. Courtesy of the artist and Asia Motion.

Tucked away in the dense alleys of Phnom Penh’s historic Chinese area is the Chapel of the Sister of Providence. A church during the French colonial era, the building was converted into a prison for part of the Khmer Rouge period, after which it became a state orphanage for 20 years before closing at the turn of the century. The building continues to house former tenants and employees of the orphanage: 15 families, or around 80 people, have divided the floorplan into small, semi-private apartments under the Gothic ceiling. Photographer Sovan Philong spent one year interacting with and documenting this unique community. After establishing traditional portraits from daily life, Sovan concluded his exploration of the site by capturing ephemera that personalize the community space while serving as idiosyncratic subject matter for another kind of portrait: product advertisements, a line of NGO training certificates and human rights booklets.

Vuth Lyno, born 1982

Vuth Lyno, The Make-up Artist, Thoamada II series, 2013. Courtesy of the artist.

Over the last five years, Khmer LGBTQ individuals have become increasingly visible through public engagement and community organizing. Although Cambodia is generally a tolerant culture, with young people tending toward greater acceptance than elders, Khmer LGBTQs continue to face common forms of discrimination from family rejection and community discrimination to disproportionately poor legal protection. “Thoamada II” aspires to frame the Khmer LGBTQ community—the individuals, their families, and their memories—as thoamada, or “normal, everyday.” Artist Vuth Lyno stages two thoamada portraits: a family in a domestic setting, and a recreation and improvisation of a particular memory from a woman named Sitha, whose narrative is offered to audiences in the titles and texts accompanying a series of diptychs.

Vuth Lyno, The Salt Seeker, Thoamada II series, 2012. Courtesy of the artist.

Sitha, pictured on the left in the photograph above, describes the context of the memory she chose to reenact:

I met my wife during the Pol Pot regime when we were digging a canal opposite each other… During rice transplanting month, I went to ask for some salt from her, but she refused…During harvest month, we met again and started to talk, and we fell in love… This love is difficult, because they didn’t let us meet… After 1979, we didn’t get married properly but we created wedding rituals. I play the role of head of the family, as husband and with her as a wife, and we have adopted three children—two daughters and a son—and have six grandchildren. My children call me dad, and my grandchildren call me granddad.

Pete Pin, born 1982

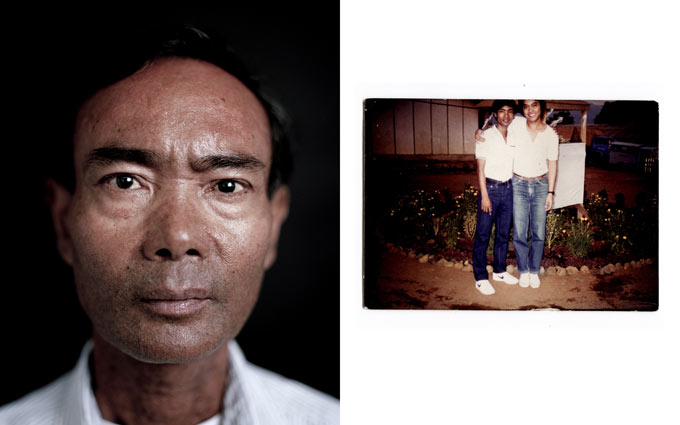

Pete Pin, Cambodian Diaspora Portraits, 2010. From left to right: My father, John Tha Pin, Stockton, CA, August 2010; Portrait of my father and his English instructor at a refugee camp in the Philippines in 1982. Courtesy of the artist.

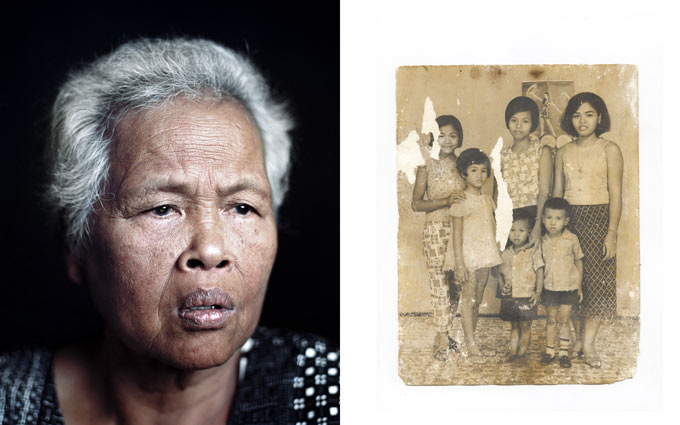

Pete Pin, Cambodian Diaspora Portraits, 2010. From left to right: My grandmother, Duong Meas, August 2010, Stockton, CA.; Family portrait circa 1973, one of only two items saved by my family from before the revolution. Courtesy of the artist.

Pete Pin’s ongoing series of diptychs place present-day portraits of individuals in conversation with images from personal archives. Produced on location via a portable studio and scanner set up in homes, community centers and temples of the Cambodian diaspora in the United States, Pin is interested how the process of making photographs within familial or community space prompts intergenerational dialogue among the very families and communities he photographs. Though audiences do not hear the private dialogues, we sense the human in the portrait and the intentionality of selection in the document. Whether in the form of photographs, certificates or airport transfer cards, such material is critical and precious—a tangible connection to memories of life once lived in Cambodia, where most images and archives were lost or destroyed during the Khmer Rouge period.

Vandy Rattana, born 1980

Vandy Rattana, Boeung Kok Eviction 6, 2008. Courtesy of the artist.

Vandy Rattana, Fire of the Year 3, 2008. Courtesy of the artist.

Vandy Rattana began his photographic career in 2005 with a concern for the lack of physical documentation of the stories, traits and monuments unique to his culture. Employing a range of analog cameras, his early serial works share a preoccupation with the everyday, as experienced by the average Cambodian. Whether depicting quiet domestic and office interiors or intense scenes of forced urban evacuations from fire or land grabbing, his work is united by a cinematic and intimate sensibility. Vandy’s recent works mark a philosophical shift in their approach to image making and historiography; his practice evolving from engaged observation to active reconstruction of narratives.

Khvay Samnang, born 1982

Khvay Samnang, Untitled, 2011. Courtesy of the artist.

Khvay Samnang, Untitled, 2011. Courtesy of the artist.

Throughout 2010, Khvay Samnang studied media sources, surveyed everyday life and scheduled nine documented performances during security guards’ lunch breaks at Phnom Penh’s lakes—vital natural hydraulic systems that have become contested sites as the Cambodian government illegally sells, privatizes and fills them with sand for commercial projects. Over 4,000 families have been evicted from both formal and informal lakeside settlements. Those who protest meager compensation packages are often abused and imprisoned. Khvay entered the lakes, among refuse, vegetation and homes in the process of being dismantled, to pour a bucket of sand over his head. This succinct act, and the resulting images and video, resist the polarizing language of media and instead offer silent spaces of reflection on complex change.

“Out of Nowhere: Photography in Cambodia,” a title borrowed from Zhuang Wubin, is presented in collaboration with IN RESIDENCE, the Visual Art program of Season of Cambodia, co-curated by Leeza Ahmady and Erin Gleeson. IN RESIDENCE is a citywide visual arts program that activates artistic practice through two-month residencies for 10 contemporary artists and one curator, alongside singular exhibitions and transdisciplinary public programs across 15 New York City arts institutions. By extending the artists’ practices as ways of generating and reflecting both experience and knowledge, IN RESIDENCE offers audiences new perspectives on Cambodia’s past and present.

The Season of Cambodia festival of which IN RESIDENCE is a part brought the work of 125 Cambodian artists to New York for April and May 2013. Season of Cambodia is an initiative of Cambodian Living Arts, a nonprofit organization based in Phnom Penh and the United States. For more information about the program, visit Season of Cambodia: IN RESIDENCE. For a complete archive of events, click here.

This is the first portion of a two-part special. To read the second, click here.