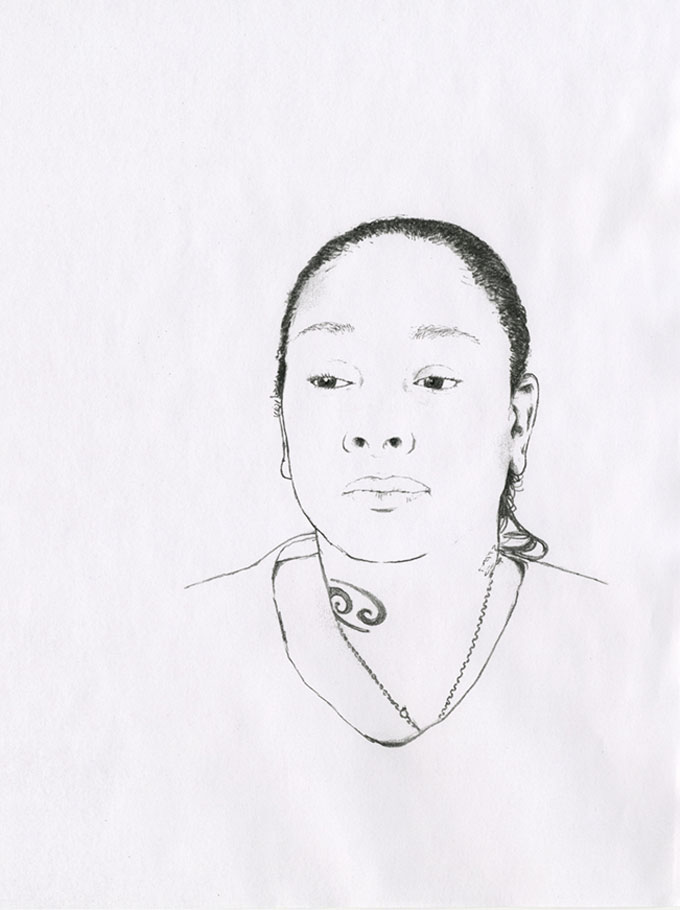

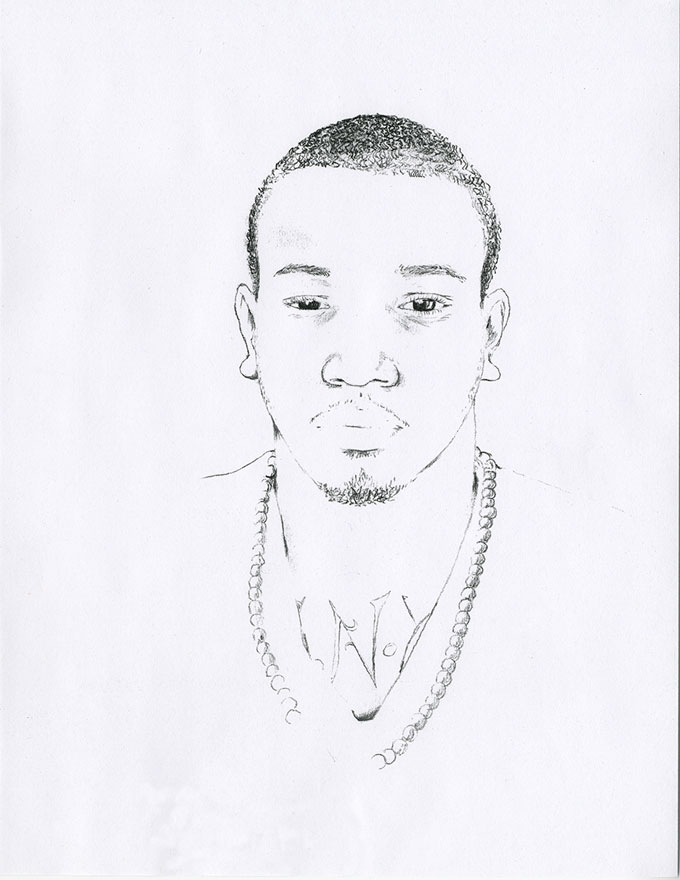

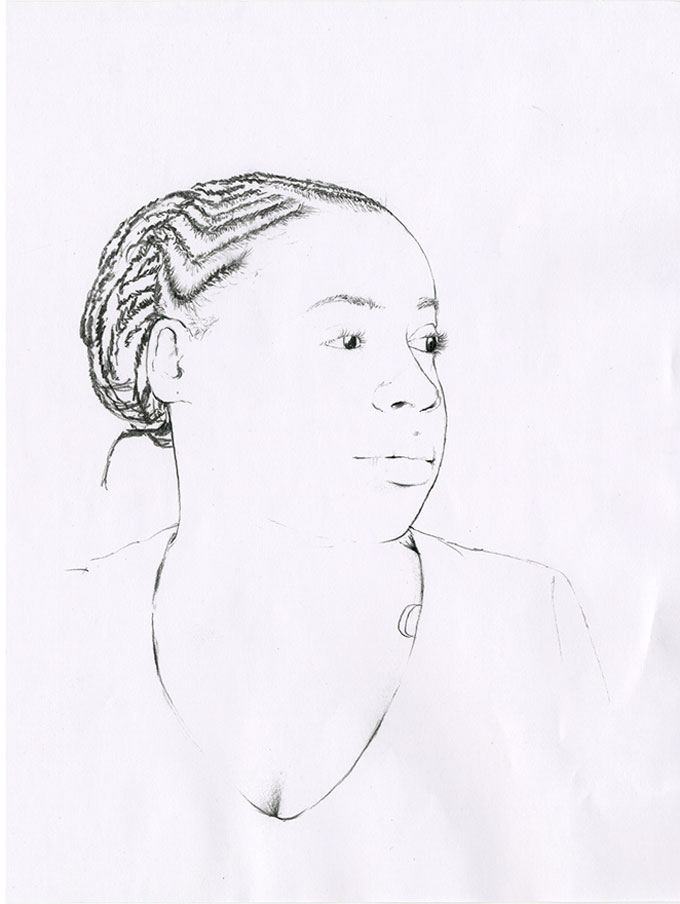

Drawing of a Rikers Island detainee by Ricardo Cortés, who runs art workshops at the New York City detention complex.

On Rikers Island it is not fruitful to be angry. For the past year I’ve run art workshops for men and women who live here, in New York City’s largest detention complex. I’ve seen anger revealed in fits and bursts, but more often I marvel at how the people I meet simply accept being locked in a cage for the most precious months and years of their lives. When someone has a family and a future, right now is the most potent moment. And right now, there are around ten thousand people maintaining extraordinary calm, incarcerated on a small island just a stone’s throw from LaGuardia Airport.

Who are they, these kind, funny, depressed, angry, anxious, brilliant, bored, calm people? Or rather, why are they here? To start, drug-related charges constitute the most common reason people are admitted into the NYC Department of Correction. Rikers is a system of jails, not prisons—designed to detain people before and during trial, or for sentences of under a year—but it’s worth noting that drug offenders also constituted the largest proportion of prison admissions nationwide in every year between 1998 and 2010. So, before landing behind bars, before shackles and before punitive segregation, many of these people were using heroin. They were selling weed. And often their skin is brown, since blacks and Latinos are sentenced for drug offenses more harshly than whites, notwithstanding similar levels of drug use.

Cortés: “I bring art materials that are otherwise contraband, such as colored pencils and markers, along with paper and coloring book pages the detainees use to write letters home, make birthday cards or simply draw with to meditate.”

Of course, race and class deeply inflect the makeup of New York City’s jails. Although the city’s total population is 23 percent black, 29 percent Hispanic and 33 percent white, the incarcerated population is 57 percent black, 33 percent Hispanic and 7 percent white. Poverty is not only a hidden root of mass incarceration; it is also a concrete factor that makes the difference between who posts bail and who languishes in jail. Three quarters of individuals incarcerated in the New York City jail system have not been convicted of the crime of which they stand accused. Most of them are here because they can’t afford bail to go home and await trial. For every ten bails set at just $500, eight defendants will go to jail. The NYC Independent Budget Office estimates the annual cost of incarcerating pre-trial detainees unable to pay their bail at $125 million.

And we will pay. It costs $167,731 to keep one person jailed here for one year. To many inmates, this figure is stunning. It seems naive but completely reasonable to think if a fraction of that budget were allocated to an individual’s education, job training, housing or health care, it would solve many of the problems that lead to an arrest in the first place. There are notable exceptions, but Rikers feels less about solving problems than about temporarily containing them. Here, inmates wait, while we pay the rising costs of their guards, utilities, food and medical costs.

Women often ask for images of cartoon characters for their kids and grandchildren.

Medical costs? Despite their costliness, jails have also become surrogate mental health institutions. According to the Department of Correction, one in three residents of NYC jails has some form of mental illness. Nationwide, more than half of all prison and jail inmates have mental health issues and 60–75 percent of youth in the juvenile justice system meet criteria for at least one mental health disorder. In the past several years, federal and state budget cuts have significantly depleted mental health services. Their replacements are inappropriate, traumatizing environments for traumatized people. A recent study of male Pennsylvania inmates found 85 percent reported being a victim of a past crime-related event, such as robbery or home invasion; more than three quarters had been physically or sexually abused. “There’s no more expensive way to treat mental illness, but it’s what we do,” says Glenn Martin, executive director of the Fortune Society, which runs a mental health clinic giving treatment to recently released Rikers inmates.

If you’re interested in issues of incarceration, you’ve read these same observations year after year. Simply put, jail sucks. Do we need it? The abolition of prisons was too radical to imagine when I first heard the idea. Now I entertain it. Of course, detainment has some utility. Some people are so violent and dangerous that we should hold them for our protection (and theirs). And I’ve met others whose arrest also stopped a downward spiral in their lives that could likely have ended in death. But instead of paying for incarceration to stop—or most likely pause—these behaviors and cumulative offenses, wouldn’t it be better to invest in infrastructure and services that might mitigate their eruption? Since preemptive and therapeutic care is often less expensive than the criminal justice system, our punitive path is stuck in an especially uncreative loop.

In the workshops, we draw together, and after a few requests, I began to draw them.

The grossest irony is that increasing levels of imprisonment may exacerbate the very problems it is intended to solve. Imagine a drug-dealer, a check forger, a prostitute or a burglar who comes to Rikers. They’re often leaving family behind, possibly as the primary breadwinner, breaking up a critical support network and causing measurable damage to spouses, siblings, parents and especially children. They’re losing a job during their incarceration, thus falling further behind in bills, rent, and ultimately housing. They’re being released after their stay with little treatment or prospects for a new job; their completed sentence may stain their record such that it’s even harder to find employment. And they’re back on the street with the same personal struggles of addiction, domestic abuse, health issues and difficulty in finding sustainable housing and legal employment. It’s not hard to guess what happens next.

Counterintuitively, when incarceration is concentrated in an area, local crime rates actually increase, according to scholars like Todd Clear, Dean of the School of Criminal Justice at Rutgers University. The escalated removal of people from a community for antisocial behavior has exactly the opposite of its intended effect: it destabilizes the community, further reducing public safety and often creating “Million Dollar Blocks.” In many neighborhoods, the pipeline to jail or prison is so intense that states are spending in excess of a million dollars a year to detain the residents of a single city block. In 2003, two blocks in the Brownsville neighborhood of Brooklyn accounted for $4.4 million in incarceration costs. The mass export of people from these communities not only affects individuals but it is also felt by the remaining population already teetering between the hustle and survival.

Young men have requested images of “love shit, hearts,” “Mickey Mouse and his girl,” and “you know, that dog and the spaghetti.”

Increasingly tenacious incarceration has been the United States’ main approach to dealing with criminal activities for the past three decades. Yet it is debatable whether this frightening reduction of the free population has had a significant impact on crime. The assumed logic of tougher sentencing is that the more people are locked up, the fewer are left on the streets to commit crimes. But the strategy of incarceration has reached a tipping point where it loses its potency as a means of crime prevention and simply becomes a failed societal norm—even a rite of passage. Every day new babies are born and new teenagers find their way to these cages. Every day the cycle repeats.

It’s perplexing why so many bristle at the idea of giving someone $25,000 in food or housing assistance, but raise no ruckus and provoke no national dialogue when we pay over $150,000 to feed and store that individual behind bars. Many people I speak with at Rikers have other family members, often a parent, with a history of incarceration. Either these prisoners have a genetic proclivity to crime (that is, to crimes that raise eyebrows from law enforcement officials, as there are very few white collar criminals here) or they have lived in social environments that severely limit their capacity to succeed—or even survive. It seems only fair that, to those whom we would punish, we first offer a reasonable chance to “make it.”

To see more portraits from Ricardo Cortés’s Rikers Island series, click here.