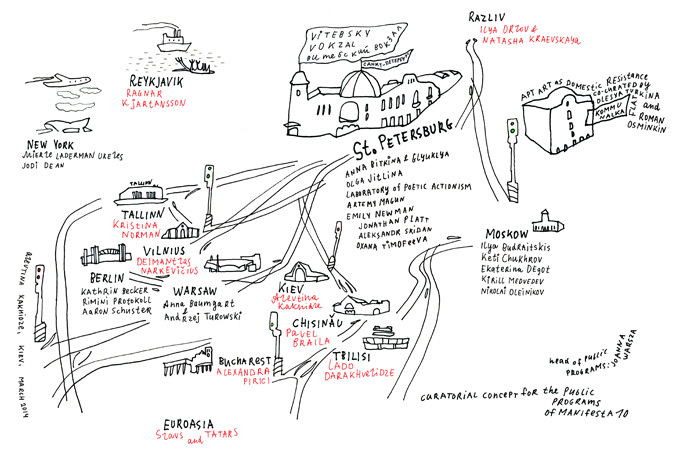

Curatorial concept of Manifesta 10’s public program, drawn by Alevtina Kakhidze, Kiev, 2014. Courtesy of the artist.

On June 28, the 10th edition of Manifesta, the roving European biennial of contemporary art, will open at the State Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg. The biennial’s choice of location has drawn impassioned criticism for at least 10 months; in August 2013, the Irish curator Noah Kelly launched a petition calling on Manifesta to “reconsider St. Petersburg as their next location” in the wake of Russia’s ban on “gay propaganda” and other discriminatory laws. Kelly’s petition set off a debate about boycotting Manifesta 10, which was later reinvigorated by Russia’s military intervention in Ukraine and annexation of Crimea.

On March 11, Manifesta 10’s head curator, Kasper König, stated that the exhibition would remain in St. Petersburg. Yet in the following days, the St. Petersburg collective Chto Delat?, which initially opposed a boycott of Manifesta, publicly withdrew its participation in the biennial.

Joanna Warsza, curator of the public program for Manifesta 10, reiterated her commitment to the show, stating: “We are confronted with the old political dilemma: engagement or disengagement? As much as we of course clearly and without doubt oppose the Russian military intervention in Crimea and the position of the Russian government, we also oppose the tone of westocentric superiority…. The projects will obviously not represent the position of the Russian government. I believe that as long as we can work in the complex manner and in the context-responsive way, as long as we—curator, artists, team—are not exposed to the self-censorship, not being intimidated or restricted, we will do so.”

In May, Warsza met with Creative Time’s chief curator, Nato Thompson, in Berlin, where they discussed the ethical and political stakes of the boycott and how artists participating in Manifesta 10 are responding to the political situation in Russia.

Nato Thompson: I am sitting in a café outside the 8th Berlin Biennale with Joanna Warsza. Two years ago Joanna was an associate curator of the 7th Berlin Biennale, whose head curator was the artist Artur Żmijewski, and they invited members of Occupy Wall Street to take part in the show. In fact Occupy camped out in the middle of the biennale’s venue, on the ground floor, which to some looked like the grave of Occupy, as Joanna was telling me earlier. The whole situation generated serious political fallout, though it was also one of the few biennials I have attended that was truly an experiment in what was possible. There were many tensions and even failures but also, I would say, productive failures.

Today there is a push to boycott Manifesta because of its venue in St. Petersburg and its relationship to Putin’s repressive politics, in particular Russia’s anti-gay laws. The boycott has garnered a great deal of attention, in a way related to but distinct from the attention surrounding the Occupy protesters at the Berlin Biennale. Joanna, it seems that political contestation is following you. I can certainly relate as a curator who works at the intersection of art, politics and activism. Conflict and controversy tend to surround your work.

Joanna Warsza: It is hard to enjoy conflict, but conflict also produces moments that might bring about a change, a repositioning of ideas. That is why you know that you have to go through it. And that is why I read the current boycott of Manifesta not as a call to quit work in Russia—because that would not help the LGBTQ community or halt the revived Cold War rhetoric—but rather as opposition to the verticality of power that St. Petersburg’s State Hermitage Museum represents and to the decision of a progressive biennial to use such a venue. Indeed, I believe the boycott is also a call to all biennials at large to be more responsive to political situations and more daring in their engagement.

Ilya Orlov and Natasha Kraevskaya, A Revolutionary Museum After Ideology, 2014. Photo of Museum Sarai (“the shed”), part of the Razliv Museum Center near St. Petersburg, copyright Razliv Museum Center, 2013.

I recognize many reasons for contemporary art practitioners to challenge the Hermitage. But I also agreed to work within these power structures. As an independent curator now associated with Manifesta, working as part of a team of foreigners in Russia, I have to reflect on how I can use this situation of being both inside and outside—how to put this responsibility to relevant use and make a point. Recently the curator Nora Sternfeld and I came up with a way of describing how we see such curating: you are a police officer and an activist at the same time.

To return to your comments about the 7th Berlin Biennale for a moment, yes, there was a courageous sense of experimentation. Actually biennials, at least since the first Havana Biennial, in 1984, have been designed as experimental platforms, in opposition to museums. With the 7th Berlin Biennale, something was shaken—business didn’t go as usual—and this is what we should be doing.

NT: So then you take on Manifesta, and here you are again…

JW: Here I am again, exactly. Manifesta, as you probably know, is a European biennial founded at the end of the Cold War, supposedly to connect East and West and present young and emerging artists. This year Manifesta has decided to go to Russia, which is a good choice, because a European biennial ostensibly connecting East and West should act in the East, not only in the relatively safe West.

St. Petersburg’s Vitebsky Station, the first train hub in Russia to connect the East and West—its name bearing homage to the famous city of the early 20th-century Russian avant-garde. The artists Warsza invited to Manifesta 10’s public program all come from former Soviet cities accessible by train from Vitebsky Station. Photo by Rustam Zagidoullin.

NT: So who called for the boycott and why?

JW: There were two waves of the boycott. The first came from the international community last summer, before I was involved with the project, because of the anti-LGBT laws in Russia. In June 2013 Putin signed a ridiculous bill banning the “propaganda of nontraditional sexual relations” among minors. Just to remind you, in the Soviet Union being gay or lesbian was forbidden and persecuted. That policy was repealed in 1993. The new anti-LGBT laws, however—together with other laws requiring NGOs to register as “foreign agents,” introducing a tax on divorce, condemning births outside of wedlock and so on—are the evident expression of a conservative turn and an oppressive political environment in Russia. It is clearly not a situation of the rule of law, but of ruling by law.

Boycotts make institutions more sensitive, vulnerable and apt to change. Institutions should not suppress them but consider the claims.

That said, we should ask some questions: What is the nature of this boycott—not going to Russia because of the anti-LGBT laws? What do you achieve exactly when you click the “I am not going” button? Do you think you are supporting the LGBTQ organizations here? Or do you rather care about raising awareness? If so, what do you accomplish through isolation?

Boycotts, these questions notwithstanding, are legitimate political tools, and though it may sound strange, I actually think it is good that they are taking place. Boycotts make institutions more sensitive, more vulnerable and more apt to change. And institutions should not suppress them but consider the claims. So I would consider the boycotts as a form of mobilization, not a form of quitting. By the way, many artists included in Manifesta 10’s main exhibition, such as Marlene Dumas and Wolfgang Tillmans, directly address the subject of LGBTQ rights as well as the nature and meaning of boycotts and the political situation at large.

NT: Is the Manifesta boycott part of a larger boycott movement around LGBTQ rights in Russia? Because the famous cultural boycott that actually was extraordinarily effective was the boycott of apartheid South Africa, and that, together with the push for divestment, was internationally known. It worked, but if boycotts are uncoordinated, they are very difficult and ineffective.

JW: There are countless crucial issues in Russian politics today that demand an outcry: the aggression in Ukraine, plutocracy, social insensitivity, the eradication of civil society and so on. But Russia will not disappear, and as Kristina Norman—one of the artists taking part in the public program—said, it is in our interest to be talking with Russian society. In the wake of Russia’s annexation of Crimea, we were confronted with a classic political dilemma: engagement or disengagement? If we hold this show in St. Petersburg, under what circumstances and to what end do we do so?

Kristina Norman, Souvenir, 2014. Photo courtesy the artist.

NT: Certainly the public perception of Russia right now is really low, wouldn’t you say? Probably the lowest it’s been in a long time.

JW: Yes, Russia-bashing is in, perhaps rightly so today.

NT: Listen, coming from a place like the United States—we receive our own share of reasonable bashing. The Bush administration didn’t do a lot for the U.S. reputation and frankly, working in this country comes with its own lion’s share of contradictions that one must work through.

JW: Now that I am working in Russia, I have to explain daily that I am absolutely critical of the Russian government and see my work here as a form of engagement with oppositional, critically minded people. I have to say, though, I wish cultural workers in the United States were immediately associated with the politics of drone warfare!

NT: I completely understand. Contestation and complicity are tensions that surround all culture making, but of course, why the lens is on Russia and not, as you point out, the United States is an important question to consider.

I believe that quitting Manifesta would be playing into the rhetoric of the Cold War. A show should absolutely go on, but it cannot go undisturbed.

JW: I would also ask, Which perception of Russia is at play here, and who is constructing this perception? My decision to stay here is addressing this construction of a Western gaze. As you know, I come from Poland, which is very Russo-skeptic, to say the least. From the moment that the conflict started, so many colleagues pressed me to leave Russia. Some wrote to me on Facebook advising me to say that I got sick or found another job…and I had my internal doubts of course, but—together with the artists to whom I have a responsibility—I decided to continue, under the condition that I would address the current political situation. I simply don’t agree with the reaction of immediate superiority of judgment.

NT: Given that you are from Warsaw, this deep Russophobia isn’t just professional—it must affect you personally too, right? A call for you to pull out of the show is not just an abstract, theoretical discussion. How is that for you?

JW: Of course it affects you. In the end we are vulnerable beings. I think you have to take a step back and understand what both your political position and your personal position are in a given context. This helps you to carry on. When you formulate this position, you find out whether you are morally disagreeing with yourself. If you are, you should step back. But if you are not, if you still believe that the projects you curate are responsive to the political reality, then that idea carries you forward and enables you to confront people who will be critical of you and ask them, “OK, you are critical, but what are you doing for this situation? If you are telling me I should step out, are you just saying this because you will feel better?”

NT: So for you the politics of engagement is negotiated and context-specific. How do the artists you have selected for the public program work in relation to this?

JW: When the Russian intervention in Ukraine and the conflict in Crimea started, I was very stressed, but then I sat down with the artists I am working with, all of whom hail from post-Soviet countries. That is the concept for the public program: to invite people from formerly Soviet cities that can be reached by train from the oldest station in St. Petersburg, like Slavs and Tatars, Deimantas Narkevičius from Vilnius, Kristina Norman from Tallinn, Alevtina Kakhidze from Kiev and Pavel Braila from Chișinău. All of us are simultaneously from nearby and from far away; therefore we are not romanticizing Russia but trying to understand our relationship to it and make a point.

Pavel Braila, Railway Catering “Prietenia,” 2014. Photo documenting the arrival of the train Prietenia (“friendship”) from Chişinău to St. Petersburg’s Vitebsky Station by Rustam Zagidoullin.

NT: Artists can choose to boycott Manifesta, but for a lot of artists the opportunity to participate in such events doesn’t come that often. Likewise for you and me these opportunities don’t always arise, so we have something to gain by taking them. For a curator to boycott the event to which she or he is invited does not go unnoticed. People in power look for a good team player—someone who doesn’t make them look bad—so if you were to join the boycott, that would be a huge decision for you. It would have much more impact for you than for people on the outside calling for the boycott. For you it would be a real job killer. Likewise for the artists who might think, “I’m not going to get invited to Manifesta ever again…I’ll be stuck in Tbilisi waiting for someone to give me a show,” right?

Crimea? Anti-LGBT laws? Political repression? These subjects are hardly discussed in [Russian] offices or in newspapers.

JW: Yeah, sure. Manifesta is also an opportunity for me and I was happy to be invited by Kasper König, a pioneer of curating public art who co-founded Skulptur Projekte Münster and, together with figures like Harald Szeemann and Jan Hoet, spearheaded the profession of curating. By accepting my position, I am part of both the structure of the Hermitage and the brand-friendly Manifesta at this particular moment in time. But in fact every curatorial situation—whether in Abu Dhabi or Shanghai or at MoMA—is problematic for different reasons. You just need to be honest in how you deal with it and how you address the terms and conditions that you have been offered (as artists did earlier this year at the Sydney Biennale).

If you are intimidated or censored, you can always leave, and your resignation will acquire a political meaning. But do not quit if it doesn’t cost you something. The privilege of having the freedom to quit actually enables us to work further. And a potential boycott would have to be a collective decision with the artists.

NT: That this boycott has come about is also intrinsically related to the kind of work you do. You are dealing with subjects that touch people. Mainstream curators never get this kind of flak. No one is taking Gagosian to task for showing Damien Hirst, for example. Politically minded art people simply do not care. But Manifesta has a political history, as do you, and people care about this legacy in a very different way. So the boycott is a sign of respect for Manifesta too. And people are deeply concerned about Russian politics. This Manifesta happened to occur at the same time as the invasion of Crimea, so it is like a perfect storm.

Alevtina Kakhidze, В Африкy гyлять / Where the Wild Things Are, 2014.

JW: It is weird to say, and it is a very tragic and unfortunate reason, but because of the annexation of Crimea and the war in Ukraine, this will be such a debated edition of Manifesta. The art will have to position itself toward this moment. I believe that quitting Manifesta would be playing into the rhetoric of the Cold War. A show should absolutely go on, but it cannot go undisturbed. It should go on showing vulnerability, affection and compassion for the situation, because otherwise you appear indifferent. There are always PR protocols and marketing structures that become completely inappropriate or useless in these situations: protecting partners, for example. It’s important to have partners, but it’s important to voice your opinion, show your concern and show your position as an institution.

NT: In terms of the temperature in St. Petersburg, so to speak, one would imagine that institutions are worried about how they’re perceived, not only internationally but also internally, within Russia’s structure of power. Can we talk about that? From the outside, it seems like everybody has to be very cautious in terms of stepping out of line. Not the same as operating in Berlin, right? Is that an accurate understanding? How is that on the ground, and how does that affect artistic practice and the institutions that support artistic practice?

JW: It is a schizophrenic experience. When you read about Russia in Western Europe, you are concerned, almost hysterical. Then you land in St. Petersburg—a city built as a mimicry of Europe, incidentally, where people settled “to play Europeans”—and … it’s as if nothing was happening. Everybody is smiling. Crimea? Anti-LGBT laws? Political repression? These subjects are hardly discussed in offices or in newspapers. Russia Today, the government-funded TV news network, presents a completely propagandistic version of current events. So you are there, and you think, “OK, I’m on the ground, but I don’t feel any urgency.” The political situation is completely elided and suppressed, and this is tragic. These are the places where art is most needed, if we believe in its political efficacy.

Alexandra Pirici, If You Don’t Want Us, We Want You, 2011. An intervention in public space in Bucharest, to be followed with interventions around the monuments of Peter the Great, Catherine the Great and the Lenin Statue at the Finland Station for Soft Power – Sculptural Additions to Petersburg Monuments, 2014. Photo courtesy the artist.

NT: How have local artists responded?

JW: As you know, the important St. Petersburg collective Chto Delat? withdrew because they thought the institution didn’t react on time; they accused the biennial of being unable to challenge an evolving political situation. And I understand that, but I deeply regret their decision to withdraw without trying to organize a solidarity show with Ukraine for Manifesta. They published their statement on Facebook, but do you think Kasper König reads Facebook? It was read only by a narrow circle of people.

NT: Do you think they should have stayed in the show and provoked the institution from within?

JW: They are planning a Russian-Ukrainian solidarity project outside of the Hermitage, but it could be so much more powerful if it took place inside it. Chto Delat? has been active in St. Petersburg for 15 years, and they have never been exhibited at the Hermitage. It could have become a very strong statement at this time, challenging the most vertical institution of art in Russia and Russian politics. They are preparing a very interesting Russian-Ukrainian summit, but the mainstream audience will not be exposed to them.

NT: But do you think the institution would have been prepared to…?

JW: Kasper König is somebody who honors artists’ positions. And this is the moment when it could have happened. It’s a moment of disturbance. It’s the opening window, so hopefully, yes. Or am I just dreaming? Of course you don’t want to be a Westerner coming in and saying, “Come on, guys, wake up.” You also want to be heard. You have to play a double game. Remember, I have to work with the city. Part of your work is to try to pull projects through, so you use a different discourse in the office, a different discourse in the art world. Some projects can reveal themselves differently once they are made. But just a short anecdote: when I went to the Cultural Office, there was one book on the table. Guess what book it was? Pick a book.

NT: What, Das Kapital or something?

JW: [Laughs.] You wish. No, it was an album of Vladimir Putin in all poses. In all seasons, in all poses.

NT: Really?

JW: There were other books on the shelves, but on the table was this absolutely horrible devotional volume to Putin, you know, white with gold letters. And then you think, what am I doing here?

NT: Or, this is going to be a tough meeting!

[Laughter.]

JW: I have been considering my position in Russia, looking at the country’s recent history and reading some of my Russian colleagues, like Ekaterina Degot, who wrote, together with Ilya Budratskis and Marta Dziewanska, a very interesting book called Post-Post-Soviet? They created a calendar of artistic and political events of the last 10 years in Russia. And they look particularly at 2007. That year the Voina group was formed, which together with Pussy Riot introduced a new kind of militant, artistic-activist approach to contemporary art. Art that doesn’t need to be exhibited in museums, art that becomes a cultural meme of sorts and spreads virally as online images, art that raises the question of what is art and what isn’t. Yet 2007 is also the moment when oligarchs like Roman Abramovich discover art, which of course has an immense influence in Russia, rendering art into entertainment. Finally 2007 is the moment when Putin makes a speech condemning NATO expansion in Eastern Europe, foreshadowing the present geopolitical standoff.

So you ask yourself again, what are you doing here? You might be in love with Pussy Riot, but you are not Pussy Riot. So here are my questions: Can art have a certain agency close to civic society? Can the collective energy generated by art be comparable to that of public assemblies and moments of “performative democracy” (to use the phrase of my colleague Elżbieta Matynia, a scholar at the New School)? The chances are small, but why not try?

Deimantas Narkevičius, Sad Songs of War, 2014. An ensemble of Tersk Cossacks from the Pyatigorsk region, circa late 19th / early 20th century.

In that spirit, Deimantas Narkevičius has prepared a concert, Sad Songs of War, with Cossack choirs from both Russia and Ukraine. Narkevičius looks at the spirit of self-determination within Cossack culture and its current vulgarized forms, which are symptomatic of the conservative turn in Russia. The Kiev-based artist Alevtina Kakhidze is introducing conflict mediation as a form of art. And the half-Russian, half-Estonian artist Kristina Norman, who has spent many years researching the Russian community in Estonia, is now doing the opposite in Russia. The conflict has generated projects that are very sharp and to the point.

NT: Your point reminds me of something that should be mentioned. Art has come a long way since the beginning of the 20th century and today, particularly among the artists with whom we collaborate, engagement with civil society is a critical element of the work. This kind of engagement is neither passive nor decorative, but rather constitutes an active intervention into a given social and political context. And the production or transformation of civil society is not a small project. But I think in some ways that is part of what art, particularly in the public sphere, can achieve.