Endre Koronczi, Ploubuter Park (installation view), 2015. Courtesy OFF-Biennale Budapest Archive

In May I had the opportunity to visit Budapest’s OFF-Biennale through a grant from the Trust for Mutual Understanding, an organization that supports creative collaborative exchange with Russia and Central and Eastern Europe. This was the second time I had visited the Central European city. In 2012 I had a chance to witness Hungary’s Revolution Day—a yearly celebration commemorating the 1848 uprising of the Magyar nationalists against the Habsburgs. The country has been convulsing from a government that looks more and more like an autocracy. This hard swerve to the right has meant that many artists there have found themselves out of favor with the leadership and iced out of desperately needed funding. Against this background, the OFF-Biennale was launched earlier this year. While in Budapest I interviewed two of the founders about the impetus behind the monthlong event.

Creative Time Reports (Marisa Mazria Katz, editor): Can you talk about the context for the OFF-Biennale?

Tijana Stepanović: The Hungarian cultural sector has always been very dependent on the state, almost exclusively so in the past decades. We find this very unhealthy, not only for economic reasons but also because when a government starts to use art and culture as a tool for its own agenda, effectively abusing art and culture, being dependent on this one source turns out to be highly problematic. This situation happened incredibly quickly in the past five years with the election of a new government formed by the right-wing Fidesz Party.

Due to the Fidesz Party’s two-thirds supermajority, it was able to change the constitution, restructure and centralize all the sectors: economy, media, banking, education, social services, health care and culture. Speaking specifically of the cultural sector, there is the so-called Hungarian Academy of Arts, which was originally a civil organization but was more like a group of friends, mostly artists, promoting traditional nationalist and Christian values. Through the changing of the constitution, this group basically became the major ruling public body overseeing the entire cultural sector and its budget, without it ever making its policy transparent and democratic.

Hajnalka Somogyi: This abuse of power showed how dependent we were on state resources. One also has to understand that despite the fact that state socialism ended 25 years ago, the Hungarian art scene was never really interested in lessening this dependency. In Hungary there isn’t a tradition of private or corporate sponsorship. It’s not self-evident that the affluent are supposed to give back to society, especially not in terms of supporting culture, much less contemporary art. This is partly due to the country’s culture and education, and visual art is especially invisible within the cultural map of Hungary. But at the same time I also think that it’s the responsibility of the scene. We didn’t really recognize our dependence on state resources as a problem, and attempts at partnering with the private sector have been sporadic and often unsuccessful.

TS: Handpicking of institution directors and artists is an important and alarming issue throughout the past several years in many cultural and other institutions throughout the country. Often a formal open call is announced, but you always know what the result will be. A prerequisite of getting a position [in government-sponsored cultural institutions] is having strong political connections and loyalties, while professional qualifications or professional vision is secondary. This is how the government makes the entire elite loyal to it, effectively stripping the cultural institutions of their professional autonomy and passing the control to political interests.

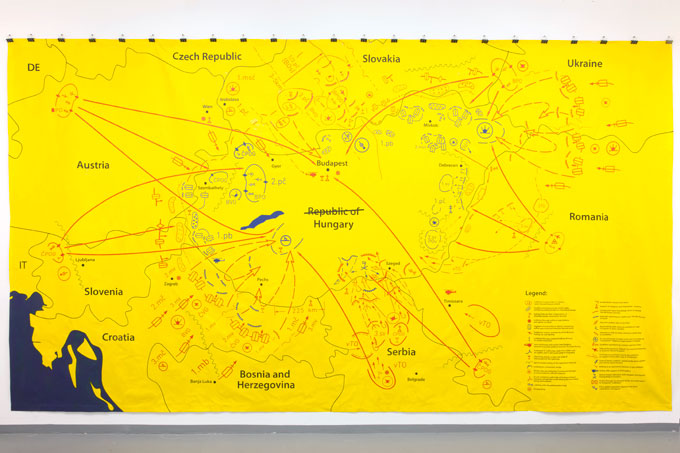

Mladen Miljanovic, Operation Hungary, 2015. Courtesy Orbital Strangers Project and OFF-Biennale Budapest Archive

CTR: What was the art scene’s reaction?

HS: The scene responded in the first four years by direct political protest, which was very brave and also very important. But in the long run it failed to yield results.

CTR: I was here to witness one of those protests in 2012 for the annual Revolution Day.

HS: These actions of the cultural sector were also backed up by an important series of intense conversations, the transit.hu Action Days, with the local scene’s stakeholders, which helped us understand our circumstances and work on ideas for survival. But then by the end of 2013, when I came up with the core idea for the OFF-Biennale with a close group of colleagues, it became clear that direct political protest was absolutely unsuccessful. On the one hand, this government is just not open to a dialogue with people—it wants to be able to impose harsh changes without debate. But on the other hand, we had to take a look at how weak we were at communication. The public media have been completely taken over by the government, and the majority of commercial media are run by private groups that have strong economic ties to the government. With these difficult conditions, we just couldn’t make our voices heard in any way.

When we worked on the strategy of the OFF-Biennale, we basically moved away from direct political action. By then we understood what role we had in this game: they make decisions, we protest, and they ignore us. The idea of the OFF-Biennale was to move the game away from this ritualistic political field, in which there was no space for democratic dialogue anymore, and back to our own field. To step out of their game, to do something unexpected. Using our own language and our own methods and expertise makes us very effective.

I think the success of this strategy was underscored by the news that we out-organized the Hungarian Academy of Arts’ flagship event, the National Salon. When we were protesting just two years ago, no one could have imagined that they would have changed their date to not interfere with us.

Curators and team leaders for OFF-Biennale. Courtesy Szilvia Márton anf OFF-Biennale Budapest Archive.

CTR: What are some of the effects you noticed after shifting strategically away from protests?

TS: After a few years of protesting and experiencing no impact because the government was so arrogant and ignorant, people started to burn out. It was a very paralyzed and depressing moment for the scene. I think these conditions are why OFF resonated with so many people. It provided a context in which people felt that they could have an impact and that they could act. This gave energy to all of us and helped to bring together different actors within the art scene who maybe hadn’t ever collaborated before. The opening weekend of OFF was perfect proof: you could feel the energy that was long missing from the scene; now there is a momentum uniting us.

CTR: Was there a particular model you had in mind for the biennale?

HS: The vision was to bring forth a large-scale international art event without any Hungarian state support, to which many local players can actively contribute. It aimed to be a catalyst for change—in financing, in communication, in working methods, in the mindsets of people. We didn’t want to and could not establish a new mega-institution; instead we built a frame within which people can start to self-organize. Accordingly, instead of the often very centralized and top-down approach of biennales, we tried to introduce a grassroots model. One of the main goals was to reach a certain audience that might be open to this kind of critical progressive art but hadn’t really met it before. Also the word “biennale” has the important promise of continuity. It’s not just a one-off thing that disappears, but we can build on it, even if the next round won’t be exactly the same.

TS: For many of us there was certainly an energy coming from this feeling of protest that led to the idea of the OFF-Biennale. I think it resonated because we had some sort of anger and energy, and we wanted to act, to create a space, an independent and free symbolic “off” space. We wanted to step outside of the politically controlled mainstream, to find our own path, to make our voices heard and show the potential and capacities of the critical art scene. Going “off” naturally meant a tighter budget but never a compromise in the professional attitude and quality. The DIY approach was partly a result of our financial situation—note that even a year ago we didn’t have any budget—but we became interested in artistic positions that work with very limited material means as a creative response to the given economic and political circumstances that influence and, for the most part, limit art production.

Drawing by Dan Perjovschi. Courtesy Dan Perjovschi.

CTR: Where did you draw your inspiration for the biennale’s name?

HS: Choosing “Off-” as a prefix was inspired by Svetlana Boym’s concept of the off-modern. And even though the theory of the off-modern doesn’t really connect to the OFF-Biennale, the idea of using the prefix “off-” rather than “anti-” or “post-” or “sub-” resonated with our need to find a term that shows that this project is not realized against something, it is not simply an anti-biennale but is an unexpected move “off the path” that might be more successful in reaching our goals. And it is also a fact that this biennale is being realized amid really “off” conditions.

CTR: How does this concept then play into the structure of the biennale?

HS: It is important to say that when we started to organize this project we agreed that we wouldn’t receive any remuneration for our work. I think it is quite “off” that so many people worked for a year and a half, one year or even five months without getting any compensation. It’s especially “off” when you consider that these people are active members of a scene in which people are usually struggling to make ends meet. It might be different in other kinds of scenes or in other kinds of social structures, but it’s certainly true in Central Europe that people don’t really have savings to live off of. We knew we would have to operate similarly to a start-up: you have to put in your own energy to start it and then try to make it sustainable.

TS: Certainly it is not a long-term goal to continue like this. Why OFF became possible even under such circumstances was that many people—some 700 who made OFF possible—felt this momentum. Staying away from the state, still being able to do something big, is something people really wanted. The passion came from the common mission that we could achieve only together. But certainly the fact that we didn’t even apply for and wouldn’t accept Hungarian state money when organizing such a large-scale event is completely “off” in itself.

Not only didn’t we use Hungarian state money, but we also didn’t work with venues that are run by the state. This is because most venues that have some infrastructure are all somehow connected to the state. We had to find venues that met our needs, and in the end we had 136 different venues in and beyond Budapest and also abroad. As you can imagine, it was a huge, huge effort. But in the end the challenge of working this way became one of the most meaningful aspects of the OFF-Biennale.

Left: István Csákány, Isolator Show (installation view) , 2015. Right: Adrian Paci, Horizontal Standings Show (installation view), 2015. Courtesy The Orbital Strangers Project and OFF-Biennale Budapest Archive

CTR: I want to talk about the artists who participated in the show, and from what I’ve seen, you’re working with a diverse group of artists, in both their backgrounds and the type of work they do. You’ve chosen to exhibit in typical settings such as galleries, but then you’re also working in places like the Center for Stamp Collecting or in the garage of the former Post Palace. How did you settle on the idea of working with so many different kinds of venues and artists?

TS: I think the variety was due to the nature of the process because the initial idea was so much the opposite of common biennial models. We decided not to directly invite artists in the first round but instead asked curators, organizers, NGOs, art spaces and collectives to propose projects and invite artists they wanted to work with. These were akin to autonomous projects, with OFF acting as an umbrella that basically joins these forces. These project organizers, together with the artists they had invited, were responsible for the production and implementation of their own projects, and in some cases they already had some spaces they were working with, or they were looking for interesting spaces where they could realize their projects. It was also important for us to create a pretty flat network of projects instead of having one or two “masterminds” who curate the entire biennale. We definitely did not want to invite a superstar curator from abroad because this biennial is rooted in and grew out of the local situation, and so we wanted it to be executed by local people and artists.

CTR: Ultimately, what was your goal for the event?

HS: The goal of the OFF-Biennale is to activate the scene and to find new ways of surviving under these circumstances. This is why it was very important that instead of curating a huge show, we let people add their individual voices to the whole image. So while we did invite artists as well, the point was that we didn’t invite artistic products but instead encouraged independent complex projects that had people taking care of them.

The RandomRoutines, Isolator show (installation view, 2015. Courtesy The Orbital Strangers Project and OFF-Biennale Budapest Archive

CTR: Will the project always have a focus on Hungary?

TS: Being rooted in local problems does not mean that OFF is not international. In fact, being embedded in the international discourse and working internationally is a sine qua non and is also part of the “survival strategy” here. If you look at the roster of artists presented, you’ll see that the first OFF-Biennale is very international. We have artists and curators from 25 countries. As the artist Dan Perjovschi said, this is one of the very few biennales in which the percentage of local artists is considerably higher than that of foreign artists. For the first iteration, it’s true that we decided to focus on the Central-Eastern European region and the Balkans. It was partly for practical reasons because, while we do have a very strong international network, it’s especially strong in this region. Also we felt that our colleagues—artists and curators from this region—would more easily resonate with our conditions and understand the circumstances we are in, what we work with and what we can offer.

HS: As for the future, at the close of the biennale we will immediately start evaluating it with other participants. Whatever form the OFF-Biennale will take in the future, it should always be rooted in the local problems and should always be structured to help the local scene. It is essential for us to keep it flexible and be open to change.