Photo by Michael Gerace

With the world’s attention on the global climate negotiations in Paris, climate-displaced communities like Kivalina—a 467-person, 27-acre barrier island village on the coast of Iñupiaq Alaska—are moving forward on their own accord. Not waiting for policy solutions from above, Kivalina is forging alliances beyond the state to activate resources and possibilities for village relocation that otherwise would not exist. If Paris is the official response of global governments to climate change, the strategies composed by Kivalina and other frontline communities represent an “alter-global” approach, a form of globalization from below. On the front lines, people are making their own futures in a climate-changed world.

From disruptions to animal migration to the loss of essential sea-ice hunting grounds and a changing coastline, climate change is of great concern in Kivalina and many other villages across Alaska. But climate change is only the most recent factor in Kivalina’s struggle to relocate, an effort that began a century ago, after the federal government forcibly settled a seminomadic indigenous nation onto a precarious barrier island. In a village where multigenerational families are now crowded into homes without running water and toilets, and where government agencies hold meetings about the community’s future in offices more than 600 miles away, in Anchorage, Kivalina’s people carry a host of unmet desires and demands that precede the world’s shared concern for climate change.

Even as global social movements call upon the world to do better, the best-case scenario for the voluntary emissions reductions pledged in Paris will fail to keep global average temperatures below the 2 degree Celsius threshold needed to avert “dangerous” climate change. And proposals to create a centralized international agency to deal with climate-displaced communities have been abandoned. Around the world, government responses have been fundamentally mismatched to the size and nature of global climate impacts. In Alaska, following President Obama’s visit to the Arctic, the White House announced an undersize $2 million commitment to turn the Denali Commission, a federal-state agency that was nearly defunct, into a “one-stop shop” for village relocation. Alaska governor Bill Walker used his recent visit to Kivalina to justify his perverse plan to ramp up fossil fuel extraction offshore and in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge to pay for the rising costs of adapting to climate change.

We’ve seen that for Kivalina and many other displaced communities, the realities of climate change have exposed the limitations of existing forms of governance and the roots of long-standing economic, social and environmental injustices. Alternative frontline strategies have not only begun to produce movement on relocation but have also become a frontier for greater local autonomy, self-determination and flourishing.

People in climate-displaced communities are taking control of their own relocation-planning processes and composing their own futures. Even as Kivalina demands government recognition of and responsibility for its displacement, in recent years self-organized groups and village councils have also been building alliances beyond the state. Through these “alter-global” networks, Kivalina is expanding the possibilities for its relocation, making space to include its cultural, political and economic desires in the process.

In collaboration with Re-Locate, a transdisciplinary social arts collective, Kivalina’s people are transforming their village community center to house the Center for Global Responsibility for Climate Displacement and Kivalina Relocation Planning. The center will host an in-village planning process and gatherings of climate-affected communities from across Alaska and around the world. Together, we are fundraising, rebuilding and planning for the village’s future. We’re designing and building decentralized and relocatable water and sanitation infrastructure. And we’re using digital media to share the stories, histories and dreams of Kivalina’s people—all grounded in the everyday life of the community.

Halfway around the world, in the South Pacific, an elders’ council in the Carteret Islands is undertaking a similar effort. When they saw how slow and ineffective the government relocation plans were, they formed the group Tulele Peisa (“sailing the waves on our own”) and allied themselves with nonstate partners from around the world. Tulele Peisa created a voluntary relocation plan to help families move from their atolls to the mainland and establish connections and build homes there without reliance on government support.

It’s no longer a question of whether governments understand or acknowledge the severity of climate change and its impacts on communities, it’s whether the problem can be addressed by the same centralized and extractive “dominant culture” logics that caused it in the first place. Governments ought to make good on their historic responsibilities by leveraging money and technological capacity to mobilize people and materials, but they must do so in response to the particular demands of frontline communities. In these early post-climate days, displaced communities—in addition to building coalitions beyond the state—have begun to insist that governments learn to work from within the plans and visions that these communities design for themselves.

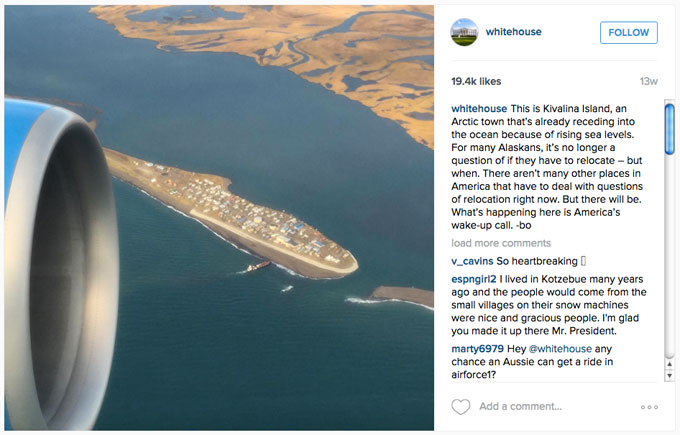

During President Obama’s trip to Alaska in August, he posted this photo of Kivalina from the window of Air Force One to Instagram.