William Forsythe

Over the course of his distinguished choreographic career, William Forsythe has become known for his creation of an idiosyncratic structural lexicon of movement. These “improvisation technologies,” as he has termed them, form the basis for the collaborative, experimental process through which he and his company develop most of their pieces. Forsythe’s approach turns his dancers’ bodies into physical echo chambers, concentrating their energies back upon themselves. The resulting pieces are accumulations of reverberating movements that pose a self-reflexive challenge as to how we understand the space of our bodies.

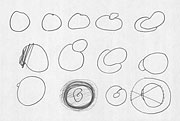

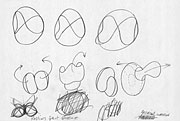

In the sketches pictured here, Forsythe tries to envision turning his eyeballs inside out. The inspiration for this mind-bending exercise derives from the work of Bernard Morin, the blind French mathematician who demonstrated in the 1960s how a sphere could be turned inside out. It also refers to what the blind French resistance fighter and writer Jacques Lusseyran said of his own mental arena: “[The] screen [of my mind] was always as big as I needed it to be. Because it was nowhere in space it was everywhere at the same time.”1

Forsythe finds in this paradox an omniscient self-awareness that parallels his experience of the dancing body. For “Plain of Heaven,” he choreographs a new piece that forces the spatial imagination of a single performer to evolve and adapt. The dancer weaves among a field of hanging pendula, keeping them in motion but avoiding them, making manifest our circular and symbiotic relationship with the space around us.

1. Oliver Sachs, “The Mind’s Eye,” The New Yorker, July 28, 2003, 48-59.

Brock Labrenz in William Forsythe's six-hour piece

credit: Don Daniels

Sketches for Nowhere and Everywhere at the Same Time, 2005

Forsythe talks about his process, inspiration, and working with performer Brock Labrenz.