By Jakob Boeskov

THE FUTURE OF CINEMA

I am in New York and it is the end of December. I look out the window where slow, white snowflakes move in one direction and yellow cabs move in another. I will soon go to Africa. I make a cup of tea and try to focus my mind. The idea is simple: I have already written a script for a short movie. The story is about and an all-out confrontation between an Afro-Scandinavian terrorist group and the Nigerian police. The group is called the Afro-Icelandic Liberation front and they are fighting for the oppressed people of the Niger delta. You know about the Niger delta, right? It is one of the main oil producing regions in the world, and there is a lot of action going on there. Hooded "oil rebels" dressed in black clothes kidnap and kill white oil people. Their style of fashion is sort of like Black Panthers meets Al Qaeda. Pretty cool in fact.

Anyway, in the story the group has kidnapped a white CEO. When Nigerian police attack the group, all hell breaks loose. I will play Dr. Cruel, the manic and violent leader of the group.

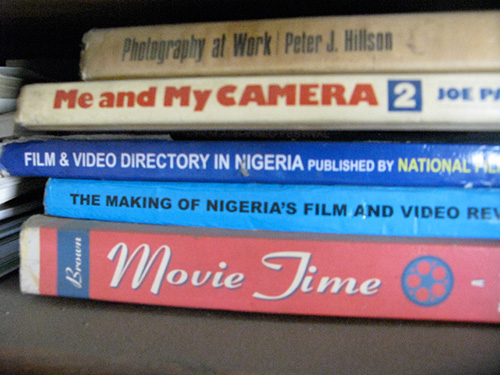

A colorful setting, as they say, but more than that. Nigeria is where the future of cinema is. Forget about Hollywood, pay attention to Nollywood! A cinematic culture that can come up with titles such as "Hitler: King of the Campus" (a college drama about a campus cult leader called Hitler) deserves investigation. Not only are the titles great, but the production circumstances are even better. I have heard that in Nollywood they shoot a movie in 10 days, and that everything is digital. This low-budget cinema is something that Godard or Lars Von Trier might have dreamed up. In Nollywood these avant-garde ideas are implemented as a national industry standard. For me, the sped-up process of filmmaking is deeply fascinating. For anyone who has been through the painfully slow speed of European film production (my first film took 4 years to fund!) this culture looks very attractive indeed. Obviously Nollywood is where it is at. This is where I want to go, it is from Africa that European cinema must be saved.

FLIGHT 287 TO LAGOS, NIGERIA

I sit inside the plane, not many people on board. I turn on the entertainment system. There are 2 movie channels: one named Hollywood, one named Nollywood. I look around and notice that I am the only white guy on board. The whole experience is quite thrilling. I can’t wait to go to an official terrorist country. It will be a totally new experience for me.

I reach down and pick up the Nigerian paper I bought. The front page is about the Nigerian president who has been absent from the country for more than 60 days, apparently spending his time in a life support machine in Saudi Arabia. On the next page there is a story from the Niger delta. The photos show half-naked children playing in polluted streets, and a landscape devasted by oil production. The children look happy and healthy, even though they lounge around in an apocalyptic landscape. The images are a bit upsetting, which is strange because normally when I see pictures of poor African children I feel absolute nothing—I only think of tasteless Michel Jackson videos or one of those annoying aid commercials that you find in the New Yorker where cute and sad-eyed African children stare into the camera. But this feels different because the publication I am holding in my hand is African. I wonder if my cinematic journey might be considered a bit tasteless.

I mean, I am basically coming to a country where wealth is siphoned off by a coalition of Western oil corporations and a small Nigerian elite. And I use the struggle of the Nigerian people as a cheap background, for what? For a weird action-art video. Can you come to a struggling people and make fun of their struggle while it takes place?

MURTALLAH MUHAMMAD AIRPORT

The first thing I notice when I step off the plane is that the country smells great. Lagos smells like Barcelona—decaying, moldy buildings and human sweat. I like it. It’s a good sign. People also turn out to be super nice. Outside the terminal, a guy lends me his cell phone so that I can call my contact, the Nollywood director Mr. Teco Benson. I look around at the people outside the terminal and see only kind and intelligent faces. What is this bullshit about Nigeria being a dangerous country? This country is not dangerous; not to me anyway. There are many policemen—and although they might be corrupt and cruel, they look rather relaxed. Some of them have even painted their Kalsnikovs in funky African colors. I don't notice any plainclothes policemen.

Five minutes later I meet Mr. Teco Benson. He arrives alone and he has good eyes and an infectious laugh. He helps me to get my luggage into his car. We drive onto the highway, passing hordes of street merchants and policemen. Next to a palm tree I see a guy sleeping in a half-open shack.

"Like a miracle you came from the sky,” Teco says, and laughs. His Blackberry has a Bob Marley ringtone. Teco is a key player in Nollywood and has films such as Blood Diamonds, Danger Signal, and Born 2 Suffer on his CV. Nollywood mostly focuses on romantic melodramas but Teco is one of the first Nollywood directors to go for action.

We drive into Lagos, talking about the wonders of the internet. It’s hot here. It feels nice.

MR. BENSON’S OFFICE

The vibe around the production is good. Everybody has been nice and nobody has found it tasteless that the story is about oil rebels. I met a guy from the Niger delta who told me that the oil rebels have turned into crooks—that they have recently started working with the government.

So yes, the vibe around the production is good. Maybe too good. I have been in Nigeria for 3 days now and not much has happened. I guess we’re in the process of casting. There are a lot of people coming and going but since most conversations take place in the Igbo language, I have a hard time figuring out what is social small talk and what is work. I spend a lot of time on the balcony looking, hypnotized, out into the spectacular traffic.

I am worried that I haven’t seen any props or locations, but Teco assures me that it is not going to be a problem. We‘ll rent the weapons from the police today. I go for a walk into the neighborhood. What are we going to do about the guy playing the white hostage? Can we use makeup to make a black guy look white? I guess I’ll have to be patient and let things unfold at their own speed.

SOMEWHERE IN LAGOS

We have finally started shooting. We’ve been at it since 8 in the morning and now it’s almost midnight. In front of our location, pieces of meat sizzle on top of small fires. Goats jump about and people shout. It is evening and the traffic is heavy. Hummers, jeeps, and beat-up mini-busses crammed full of people move slowly along the dirt road, cars honking, people screaming. Everything is dark, no streetlights, and no electricity. We get our electricity from a generator. We are filming in a medium-sized office, inside a decaying office building. The room is full of actors, crew, and gear. On the table are weapons and fake explosives. My brother sits on a chair. We couldn’t find a white actor and now I have convinced my brother, who happens to be a pilot for a Nigerian airline, to do the job. I don’t like that he’s here. It’s not advisable to have family on the set; acting is a delicate thing. I am wearing cheap wraparound sunglasses, feeling a bit worn out. Behind me hangs a black banner that reads:

THE AFRO-ICELANDIC LIBERATION FRONT

I am looking into the camera, adjusting my stupid sunglasses, wiping sweat from my face, trying to remind myself that what I am dingo is very important: a radical change to the history of cinema. Behind the camera is Teco and the photographer, a sympathetic Yoruba man in his forties.

It has been a long day and Teco has surely delivered. He really is the finest action director in Nollywood. We have filmed chases and fights. I have destroyed a pair of my pants in one of my amazing stunt moves. He has been great to work with. He has an ability to make actors and crew feel good, even when he shouts at them. But it is late now and everybody is tired.

Just as we’re wrapping up a scene, I hear the sound of a generator dying and the room goes black. The production manager runs down to the street to look for black market fuel. There is a fuel crisis in Nigeria because of the absence of the president and... well, it’s a long story.

I go to the window and light a cigarette. The room is dark, lit only by the cell phones from the actors and the crew. The mood in the room is intense, but okay, I guess. People talk low, or are silent. The production manager is back, looking triumphant. He has managed to buy some fuel in the street, and the generator is running again. The lights are turned on. Back to work.

IS IT SAFE?

Now it is time for us to do the last scene where I kill the hostage, who is played by my brother. I will kill him by shooting him in the chest. That is the plan, I think. The makeup guy straps a cardboard device to my brother’s chest. On the cardboard is written in white paint: "Lord Father" and an intricate system of small explosive devices is strapped to the board. My brother looks nervous and confused.

The actor Osita Iheme, who though small in size is one of Nollywood’s biggest stars, hands me a gun. The gun is real, but is not working. I position myself in front of my brother, who now looks down on the bulging homemade explosive plate and asks me if it is safe. My brother tells me that he thinks it is a good idea to have a fire extinguisher if he catches fire. Wearily, with the gun in my hand, I go over to Teco and tell him that my brother is nervous that he will catch fire. Teco breaks out in a huge laugh and smiles at me, telling me not to worry, that he is a good man, that he works for God and not the Devil.

I go back to my brother, tell him he will be okay, and put a blindfold over his eyes. I watch as two special effects crewmembers ignite the explosives. Fake blood spurts from his chest. An actress lifts the blindfold from my brother’s head and he smiles. We cheer and call it a day.

NOLLYWOOD FOREVER

Filmmaking in Nigeria is truly amazing. For a minimal price it is possible to make a movie here. We are talking 10% of the cost of making a movie in Scandinavia or the US. There are many reasons why it is cheap. No unions. No insurance. No middlemen to rent out equipment and software at jacked up prices. No megalomaniacal "stars" whose salaries eat up the budget. No expensive fees for lawyers and copyright holders.

In Nigeria, film is created with the tools at hand. I can't help thinking about the punk musicians in the late seventies who rebelled against the elaborate and expensive studio albums of their time—which these musicians saw as an elitist corruption of the raw energy of rock and roll. Some of these musicians looked back to the fifties in their search for a more direct music and some looked to the so-called third world, where music was cheap and fast and honest.

You see there is no need to leave cinema in the hands of big business, as is the case in the US, or in the hands of a cultural beaurocracy, as is the case in Europe. Everybody can make a film. Everybody, even in Africa, has access to a video camera. Even if you can’t afford an HD camera, you can use what is built into your phone. From now on, the film industries must get ready for nothing less than the democratization of cinema. After YouTube and cell phone cameras and free editing software there really is no way back. From now on, everybody is a director.

THE END

Teco drives me to the airport. It is time to go back to New York. We say goodbye; it feels sad. I am leaving Nigeria and I am leaving Lagos. What a great city. I really had a great time here! I enjoyed the Nigerian rock and roll way of movie making. Many artists in Europe and the US have started to make feature length films now, for the same reasons that the people in Nollywood do it: because they can, because technology has made it possible. So God bless Sony and Final Cut Pro and the falling cost of home computers. The genie has been let out the bottle and now it can't be stuffed back in. Nollywood will never die.

|

|