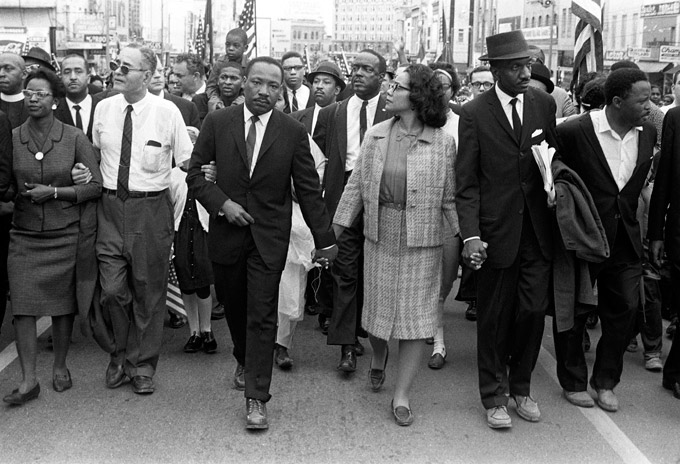

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. arrives in Montgomery, AL on March 25, 1965 at the culmination of the Selma-to-Montgomery march. Pictured from left, Ralph Bunche, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Coretta Scott King, Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth, Hosea Williams. Photo by Morton Broffman/Getty Images, 1965.

Until the United States deals with its original sin, which is that its wealth was built on violence and slavery, there will continue to be conflict between blacks and whites, between the haves and the have-nots. Until there’s a recognition and understanding of that foundational violence, the problems of racial discrimination and social inequality will endure from one generation to the next, even if their exact presentation changes.

There are folks actively trying to roll back the clock by suppressing people’s votes, by seeing to it that multitudes of poor people and people of color don’t have access to the American political system. The GOP members and conservative justices who are trying to make sure that people don’t vote are no different from George Wallace in his day. They may say different things, but when the Supreme Court struck down key parts of the Voting Rights Act claiming that we no longer need the protections won through the Selma-to-Montgomery marches, it proved that we are still fighting the same battles today that we were 50 years ago. Those who struck down—or applauded the courts when it struck down—parts of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 are the same people who, if they were in the legislature 50 years ago, would never have voted for it in the first place.

And just because we can now honor the victims of past injustices doesn’t mean that the struggle is over.

Wendell Pierce attends the New York premiere of Selma at Ziegfeld Theater on December 14, 2014 in New York City. Photo by Noam Galai/WireImage, 2014.

Too often we think about the civil rights movement in quaint, romanticized terms: we picture black men and women defiantly drinking from whites-only water fountains, sitting at lunch counters while ketchup and sugar are poured on their heads or refusing to sit at the back of a bus, as Rosa Parks and Claudette Colvin did. But the civil rights movement took place during an era of domestic terrorism: people of color were continually being murdered by their white neighbors. And though the Civil Rights Act of 1964 finally brought an end to segregation, it did not stop the practice of excluding African-Americans from exercising their right to vote—the most important right we have, since elections impact almost every aspect of our lives. In March 1965 the struggle was incomplete. There was blood on the ballot box.

That’s where we as a country were 50 years ago, as civil rights organizers prepared to march the 54 miles from Selma to Montgomery to honor the recently slain church deacon Jimmie Lee Jackson and all the other nonviolent activists shot and killed by police and white vigilantes. On the front line of the battle for self-determination, those involved weren’t wondering if there would be violence and death but when there would be violence and death. Martin Luther King Jr. said, “If a man has not discovered something that he will die for, he isn’t fit to live.”

Reverend Hosea Williams, whom I was honored to play in Ava DuVernay’s film Selma, exemplified this courage. He was a leader with a soldier’s spirit—even nicknamed Castro because he was always ready for the fight, and there were times that he had to be reminded that theirs was a nonviolent movement. But he was also a compassionate and spiritual man whose impact continues to be felt through the Hosea Feed the Hungry project, a charity he started that is now one of the largest social-service organizations in North America.

Like my father, Williams served in a segregated army unit during World War II. Imagine risking your life for freedoms and democratic ideals to which you personally are denied access by the government for whom you fight. I had an uncle from Louisiana who died in World War I for a country that did not let him go to school past the sixth grade, that didn’t recognize his marriage and that prevented him from voting and owning land. Yet he died for that country because he believed in what it could become. I could never fight for a country that I think might come around toward seeing me as a full citizen one day. Yet so many did. I wish I could have even a small part of their moral fortitude.

Countless faceless and nameless souls died with no one by their sides except their executioners. What matters now is that they are honored.

The men and women of the civil rights movement knew, just as soldiers know, that there was going to be bloodshed. But they also knew that their cause was worth risking their lives for. There is no better definition of courage: it is acting not in the absence of fear, but in the face of fear.

Selma is, in part, a film about the activists at Selma and in the civil rights movement who carried that courage forward. It is also about publicly remembering the many people who died alone on dark highways or on the banks of the Alabama River at night, with nooses around their necks or guns at their heads, thinking that they would be lost forever. Countless faceless and nameless souls died with no one by their sides except their executioners. What matters now is that they are honored—not just by this film, or by one day of remembrance, but by how we continue to enshrine in our laws the freedoms that they were denied and for which they and so many others fought.

When we finished shooting Selma, all I could think about was those nameless souls at the bottom of the Alabama River who secretly and quietly and spiritually spoke to me, saying, Wendell, don’t forget us. Tell our story. I’m still trying.

This piece, commissioned by Creative Time Reports, has also been published in The Guardian.