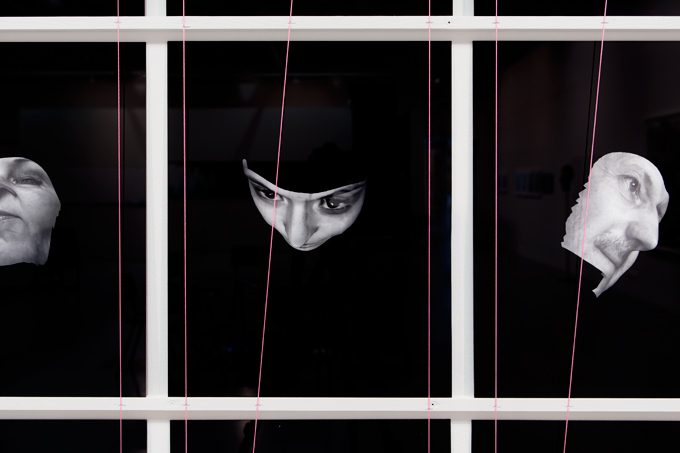

Broomberg and Chanarin, Shtik Fleisch Mit Tzvei Eigen (detail), 2014.

The work of collaborators Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin frequently involves the two artists embedding themselves within institutional structures—often at an institution’s behest—and then working from the inside to subvert conversations in ways no one could have anticipated. For proof take their most recent project, Shtik Fleisch Mit Tzvei Eigen (the title is a Yiddish insult that translates as “Piece of meat with two eyes”). This portrait series of faces spookily floating against stark black backdrops was created after the duo went to Russia to work with a company devising facial recognition software to be used by Moscow’s public security and border control surveillance. The snapshots generated by the technology, which uses data from a number of cameras to build a 3-D model of the subject’s head, have been cleared to be used as evidence in a court of law. These images can be generated even if someone’s face is captured only partially. Even more ominous, the cameras used by the technology are so small that people may never even know that they have been photographed.

For the Shtik series, Broomberg and Chanarin created portraits of 120 Russians, including Pussy Riot member Yekaterina Samutsevich. As the artists learned, the only way to disrupt the nefarious technology in question is to cover one’s face using a balaclava. And so, in typical Broomberg and Chanarin style, the two organized knitting circles at many of the galleries where the work was exhibited so that people could concoct their very own woolly face masks.

I first saw the work when visiting Surveillance.02, a show curated by Liza Faktor and Anna Van Lenten at Dubai’s East Wing gallery. The following interview, which took place over the phone, covers the span of Broomberg and Chanarin’s partnership and spotlights a number of works from their arresting oeuvre—one that I have long admired.

Creative Time Reports (Marisa Mazria Katz, editor): I thought we could begin with something that was said at a panel we recently hosted on the intersections of art and activism. One of the artists who was there suggested that art can provide an umbrella for political action, allowing for things to happen in situations in which more direct forms of action might provoke anger or a response from authorities. This made sense to me in relation to your work, which often involves subtly subverting the structures of the various institutions you’re invited to do projects with. So I wanted to ask you how you see art as a vehicle that allows you to ask questions that maybe somebody who isn’t an artist cannot ask as directly.

Adam Broomberg: A good example is the work we did in Afghanistan, The Day Nobody Died, during which we were embedded with the British Army. Here, of course, it was somewhat more complicated, because we were pretending to be journalists, and if we had said we were artists, we would not have been given permission to be there. The state feels more in control of journalists than of artists, who are not really answering to anybody. With journalism it’s almost like making public art. There’s a level of critique that you’re allowed to achieve, but you can’t go beyond that. We want to operate in a more critical space. But to respond more generally to your question, I think talking about art as if it’s just one thing is very difficult, since there are so many different kinds of artists and different kinds of audiences. You can take a work made in Russia but intended to be shown in Western Europe and bring it back to Russia, and it suddenly becomes another beast.

Broomberg & Chanarin, The Day Nobody Died, 2008.

CTR: On that note, can you talk about the piece you did using facial recognition software developed in Moscow? I’m interested in hearing about the exhibition history of the work, but perhaps you could start by discussing your preparation for the project and where the Weimar photographer August Sander comes into it.

AB: Two summers ago we stumbled on this surveillance technology, which uses a number of different hidden cameras to create a masklike composite of your face. What’s interesting and also frightening about this technology is that you’re not aware that it’s photographing you. Actually you’re not even really being photographed; it’s just that your visual data is being analyzed and stored for future use. Because of the multiple camera angles, the system is able to generate a frontal image of your face no matter which direction you’re looking in. Those who are captured by the device are thus reduced to a very passive form of subjectivity. We knew we wanted to co-opt this technology, but we were still looking for a way to frame the project. That’s where Sander comes in. We took his People of the Twentieth Century, in which he photographed everyone from the banker to the baker to the artist to the artist’s wife to the vagabond, and we cast those roles using people living in Moscow. So, for example, we had Yekaterina Samutsevich from Pussy Riot play the revolutionary and Lev Rubinstein, the conceptual poet and activist, play the poet. I think the particular choice of characters we made suggests the politics of the project. Rather than celebrating the technology, it’s very anxious about it.

Broomberg & Chanarin, Shtik Fleisch Mit Tzvei Eigen (installation view), 2014.

We were meant to show the work at the Science Museum in London, which has built a giant new wing dedicated to photography. But while the show was still being planned, they came to us and asked us if we could do them a favor. At the time they were in the process of negotiating with the Russian government to have the biggest show ever of space hardware, with objects like the Sputnik satellite and gear from the International Space Station. What they wanted was for us to avoid any mention of Russia and of Pussy Riot and not to discuss the sexuality of X and Y person. So of course the next day we did an interview with the Guardian, and apart from the sexuality of the persons in question, we mentioned everything. And in response they canceled the show.

It’s interesting to see how a museum that’s dedicated to revealing the truth ends up shying away from this material. They’re able to show how this object went to space and that it spent this amount of time there, whereas our work is much more ambiguous and doesn’t conform to the narratives of that institution. But you know we were actually relieved when the show was canceled, which we suspected might happen all along. We were quite worried about presenting the work in an institution in which technology is primarily celebrated. Our gesture wouldn’t necessarily have been seen as a critical or concerned response in such a venue.

CTR: This story speaks to something that happened recently here in the U.S., where a number of scientists signed an open letter calling for David Koch and other industrialists opposed to climate change legislation to be taken off the boards of science museums to which they have given money. That letter was written by the artist group Not an Alternative, which created a pop-up museum called the Natural History Museum and which has been calling for the removal of big money with ulterior agendas from cultural institutions.

AB: Yes, one has to question how far these institutions will go to stay funded.

CTR: So where has the work you’ve been describing finally ended up being shown? I know it was in Dubai, which is an interesting context given the pervasive surveillance that exists there.

AB: Yeah, of all places, right? I’m reminded of Israel’s assassination of a Hamas official at a Dubai hotel a couple of years ago, which Shumon Basar, Eyal Weizman and Jane and Louise Wilson made an artwork about. Not long after the assassination there was an edited video of it in perfect narrative order on the news and YouTube. It’s well known that the Israelis have developed facial recognition technology of the kind that the authorities in Dubai used to identify the assassins and sold it to Dubai and other countries. It was this weird little brilliant vicious circle in which the Israelis kind of caught themselves using their own technology. So in that sense Dubai was a great context for the work. But the first place we exhibited it was in a big survey show in Antwerp. For that inaugural installment of the piece, we organized a continuous knitting circle involving activists from around the Netherlands and Belgium, who came together and knitted balaclavas. The idea, although it’s slightly metaphorical, is that balaclavas are the only things left to protect you from this facial recognition technology. At the same time the knitting circles created a human interface or engagement that wasn’t being mediated by technology and was just quite lovely and old school.

Broomberg & Chanarin, Yasser Arafat, C-type contact print, 2004.

CTR: I’d like to hear more about how you ended up moving from more traditional forms of photography to the kind of work you’re doing today. Can you talk about the transitions you’ve made with your career in the past decade and a half since you started working at Colors Magazine? I’ve read about how your trip to Burundi made you reconsider the way that you were working.

AB: Yes. That was shortly after we took hold of the creative direction of the magazine. We wanted to set a new agenda, one that challenged classical notions about photography as a transparent method of recording social conditions. Our first trip on this new format was to a refugee camp in Burundi in August of 2000, seven years after the genocide of Burundian Tutsis by Hutus, which preceded the Rwandan genocide by a year. While we were there, we believed that we were being delicate and sensitive with respect to the context we were working within, and yet you never know what kind of weird power relations are going on behind the scenes. It turns out that there was a lot of suspicion on the part of the refugees in the camp as to whether we were working for the Burundian government or not, and we found out later that some of our translators, who were young men, teenagers, got beaten up—one was even cut badly—after we left the country. So I think we were very naive in that sense.

We ended up doing three years of this type of work, analyzing and photographing different enclosed communities and trying to understand how their hierarchies and structures operated and how power flows and works in these places. After Burundi we went to a refugee camp in Tanzania, a maximum-security prison in South Africa, a psychiatric hospital in Cuba, and a number of other places. The project eventually resulted in a publication titled Ghetto. But ultimately we realized that walking around with a camera implicitly places you on the side of power. It’s a catch-22. In the end whatever we produced was just kind of reinforcing the existing structure rather than challenging it.

CTR: And did that change your practice or contribute to a shift in the way you were working?

AB: Not super consciously, but yes, it did slowly start shifting us toward, first of all, resisting even making images—or figurative images at any rate. Another important catalyst came following our trip to the West Bank in Palestine, where we were invited to meet Yasser Arafat in his compound and given 15 minutes to take a lousy portrait. When we got to the airport in Tel Aviv, the security obviously knew where we had been. We had shot the portrait on 4 x 5 film, and they X-rayed the negatives maybe 30 or 40 times, going backward and forward through the machine in an apparent effort to destroy what we had done. When we got back and exposed the film, at first we were upset to see that the X-rays had left this wavy green pattern. But shortly afterward we realized that this mark was what was interesting about the image. It transformed it from being a standard official portrait into something that had been written upon by the Israeli state. They had added to this narrative and also kind of opened up the biography of the image. Instead of being about this one moment in time when the shutter clicks, it now has a longer narrative that is much more cinematic. Of course you never know how things are going to be read in 20 years or what people will be feeling about Yasser Arafat. The meaning of that image is going to shift totally out of our control, but I think it’s kind of lovely that the Israeli authorities coauthored that image.

CTR: So where are you with all of this today?

AB: Nowadays the focus is on infiltrating institutional powers, getting ourselves somehow embedded inside these systems. We are constantly doing a strange sort of flirtation with the people who are in control of the spaces we enter into. As the process unfolds, we inevitably end up in an increasingly awkward position when they start realizing that we’ve been doing a sort of performance with them, and that what we’re looking at is not what they expected us to be looking at. Once they see that it’s not the official version of their narrative that’s going to be conveyed by us, they start getting paranoid. But what we want to reveal is the embedding process itself and the way these power structures operate. We’re off soon to a military cadet camp, where children are trained in the discipline and hierarchy of the military. They don’t know it yet, but we’re taking a bouffon, a clown who is particularly vulgar and disrespectful of authority, to do a series of workshops with the kids to try and help them unlearn what they’ve been taught each day.