Curatorial Statement

To say there is a riddle lurking in the sugar-coated monument conceived by Kara Walker may be an understatement as big as the sculpture itself. A massive sphinx-turned-mammy, she stands mute, looking outward, acting perhaps as a guardian, perhaps a monument, perhaps, like the Greek sphinx of old, a devouring female terror. Yet unlike Oedipus in Sophocles’ tragedy Oedipus the King, we are not asked to answer a riddle: we do not even know what the riddle is, because this sphinx refuses to speak.

Presiding over the cavernous Domino building in seeming repose, Walker’s sphinx is a hybrid of two distinct racist stereotypes of the black female: She has the head of a kerchief-wearing black female, referencing the mythic caretaker of the domestic needs of white families, especially the raising and care of their children, but her body is a veritable caricature of the overly sexualized black woman, with prominent breasts, enormous buttocks, and protruding vulva that is quite visible from the back. If this evocation of both caregiver and sex object—complicated by her coating in white sugar—feels offensive, it is meant to. It is part of what Walker has come to be known for.

Walker has appropriated racist imagery throughout her career, frequently depicting scenes of intense violence and sex that are peculiarly—and uncomfortably—alluring. As she herself as said, she likes her work to produce a sense of “giddy discomfort.” This is our response not only to the sphinx, but also to the procession of black boys that serve as her attendants. Scaled-up versions of tchotchkes that Walker came across on Amazon, they have big, sweet eyes, and they carry bananas and baskets. Typically for Walker, they are both racist objectifications and strangely cute and compelling.

Walker has been known for problematic, discomfiting, and unresolved images of race since her breakout 1994 work Gone: An Historical Romance of Civil War as it Occurred Between the Dusky Thighs of a Young Negress and Her Heart. Exhibited at the Drawing Center, Gone comprised black paper silhouettes affixed to the wall, depicting a panoramic scene of antebellum white romance and playful black children. Yet as the title suggests, this “Historical Romance” is also one of sex and violence, and that difficult blend leaves the viewer unsettled.

Not surprisingly, Walker’s work, including Gone, has been met with controversy. During the “identity wars” of the 90s, she was thrust into the limelight as battle lines were drawn over the proper way to represent race, with some established artists calling her work racist. As recently as 2012–13, a large drawing by Walker that was displayed at the Newark Public Library brought controversy anew. Titled The moral arc of history ideally bends toward justice but just as soon as not curves back around toward barbarism, sadism and unrestrained chaos, it depicts President Obama giving a speech below a burning cross and amidst a maelstrom of activity that includes a white man shoving a black woman’s face into his crotch. Many objected to the work, and the Library covered it for two weeks in order to have time to determine how best to move forward, ultimately holding a public discussion with Walker before exhibiting the drawing again.

If the racial and sexual connotations inherent in the sphinx and her attendants were not enough, Walker’s work is also about sugar and the history of its production and trade. It is a story of slavery and a triangular trade route that ensured a sufficient quantity of slaves, of industrial power, our contemporary culture of overconsumption, and much more. In fact, in researching sugar as she developed the work, Walker looked at thousands of years of history (as evidenced by her use of a sphinx). The heart of her title, A Subtlety, refers to sugar sculptures that adorned aristocratic banquets in England and France the Middle Ages, when sugar was strictly a luxury commodity. These subtleties, which frequently represented people and events that sent political messages, were admired and then eaten by the guests. Perhaps Walker’s Subtlety is just a little less subtle.

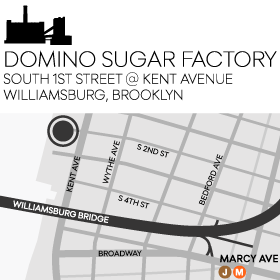

The Domino Sugar refinery is certainly an integral part of the story of sugar. Built by the Havemeyer family in 1856, by 1870 it was refining more than half of the sugar in the United States, producing over 1,200 tons of the sweet stuff every day. Every bit of the room that hosts Walker’s sculpture is covered in that history. The walls are coated in a thick, viscous molasses; the acrid smell of sugar still hangs in the air.

Walker’s gigantic temporary sugar-sculpture speaks of power, race, bodies, women, sexuality, slavery, sugar refining, sugar consumption, wealth inequity, and industrial might that uses the human body to get what it needs no matter the cost to life and limb. Looming over a plant whose entire history was one of sweetening tastes and aggregating wealth, of refining sweetness from dark to white, she stands mute, a riddle so wrapped up in the history of power and its sensual appeal that one can only stare stupefied, unable to answer.

–Nato Thompson, Chief Curator Creative Time