Curatorial Statement

Funk, God, Jazz, and Medicine: Black Radical Brooklyn launches from the site of Weeksville, a free and intentional community established in 1838 by Black citizens just eleven years after emancipation in New York. Black investors and abolitionists, including founder James Weeks, grew this intentional community to more than 500 households. This vibrant neighborhood—which included schools, churches, newspapers, and activist organizations such as the African Civilization Society—was subsumed over time by the growing city of Brooklyn. In 1968, three historic houses were “rediscovered” by prop plane thanks to a team that included artist and activist Joan Maynard. As Weeksville Heritage Center’s first Executive Director, Maynard led critical archeological digs and a community-based movement for preservation and landmarking.

This month-long exhibition draws inspiration from Weeksville’s incredible story of achieving self-determination through creating and preserving an intentional community of refuge and Black power. It also acknowledges the continued legacy of individuals, institutions, and movements that have sustained Weeksville’s core values in the contested landscape of Crown Heights and Bedford-Stuyvesant, from the nineteenth century until today.

In 2012, Rashida Bumbray and Nato Thompson began discussing a project that would explore African-American life and geographic space, and specifically the intersections of race and space in the contemporary reality of contested landscapes within our changing cities. The initial intention was to consider what cultural signposts exist as markers of Black resistance and protest to the terrorism and trauma of gentrification, stop-and-frisk, and police brutality. This led us to Weeksville, and its 150 years of creating space for humanity, dignity, and refuge in the midst of the violence of white supremacy. When we began conversations with Weeksville Heritage Center—and its then-programming and education team Elissa Blount Moorehead, Jennifer Scott, Rylee Eterginoso, and Shawn Peters—they urged taking a more deeply nuanced approach, drawn from the perspective of their own institutional positionality. The conversation moved to the development of a lens informed by self-determination and willful success, as an alternative to a narrative informed solely by struggle. With this lens intact, we began looking both back in time and into the future, inviting artists to respond to these intersections of the historical and contemporary by using existing local assets as their inspiration and directive.

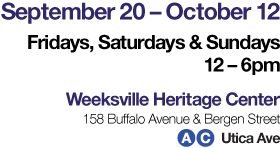

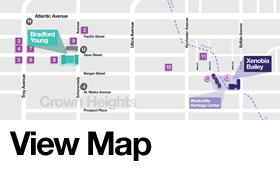

For this exhibition, the curators have invited four artists to engage the history of Weeksville in intense collaboration with four community-based organizations to create site-specific artworks on the theme “self-determination.” These partnerships pair four artists with four community partners whose commitment to self-determination embodies their long-standing historical and cultural relevance to this neighborhood. Xenobia Bailey has been working for 20 weeks with Boys & Girls High School students to produce “funk-tional” handmade furniture from recycled materials for Century 21: Bed-Stuy Rhapsody in Design: A Reconstruction Urban Remix in the Aesthetic of Funk, designed in the African-American aesthetic of Funk and installed inside one of Weeksville’s historic Hunterfly Road Homes. Bradford Young has partnered with Bethel Tabernacle AME Church to create Bynum Cutler, a film on refuge and diaspora installed inside the historic church sanctuary at P.S.83 that honors the church’s elders–the “Living Legends”–while revealing tensions between collective forgetting and changing cityscapes. Otabenga Jones & Associates, together with the Central Brooklyn Jazz Consortium, has turned the back of a 1959 pink Cadillac into OJBK FM, a community radio station that investigates connections between jazz, hip-hop, self-determination, and the history of “the East,” (1969-1985), a legendary Bed-Stuy educational, political and cultural hub. Simone Leigh has brought Brooklyn-based health and wellness practitioners to the historic Stuyvesant Mansion, creating the temporary Free People’s Medical Clinic to explore the beauty, dignity and power of Black nurses and doctors whose work is often hidden from view. Connecting all four sites is the Weeksville historical audio guide, which illuminates histories that might otherwise be invisible within the current local landscape, while allowing the artists to narrate their artworks.

These projects—which touch upon issues of community and individual enterprise, migration and memory, the radical tenets of music, and self-reliance in healthcare—hope to do so with a keen awareness of the complex relationships, histories, and economies embedded in this neighborhood. This neighborhood, with its intense history, is both a counterpoint to, and a mirror of the contested landscapes where Black people have sewn seeds, built homes, created legacies and institutions while struggling globally for sustainability.

-Nato Thompson, Rashida Bumbray, Rylee Eterginoso